|

|

|

|

|

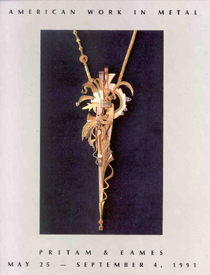

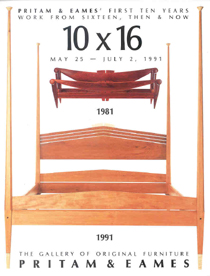

| 1981 - 1991: The First Decade | © Copyright 2005 Pritam & Eames |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The New York Times called PRITAM & EAMES the "Gallery of Original Furniture" when it opened on May 21, 1981, in a converted 19th-century steam laundry building in East Hampton, NY. In its opening show, the gallery exhibited work by makers who would become instrumental in shaping the course of the American studio furniture movement. The following selection of announcements and work from the gallery's first decade records its commitment to studio furniture and chronicles the strength and originality that establishes this field as a vital 20th century decorative art.

Founders, Bebe Pritam Johnson and Warren Eames Johnson, 1981. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Note from the editors: This document was created as a single scrolling page. It is long. If printed, the document could run from 140 to 160 pages. The editors have made every effort to align the images with their mention in the text. Words underlined in the text indicate work pictured. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Introduction |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

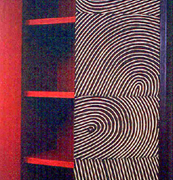

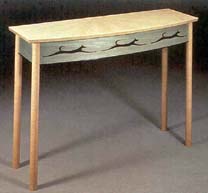

Gallery entrance door design by James Schriber |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

About Pritam & Eames |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

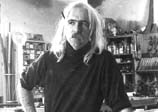

There were two early encounters that encouraged the Johnsons: in l979 they visited the Richard Kagan gallery in Philadelphia, and in 1980 they attended a furniture show hosted at the Roitman showroom in Providence. Kagan's sliver of a shop on South Street in Philadelphia was virtually the only place where an interested observer could get a sense of the maker energy percolating in the East. Kagan, a furniture maker himself, was an inspiration to the partners because of his knowledgeable selection of work. The Design Book series by Taunton Press offered another important source of information for the Johnsons, as were catalogues from museum shows such as the 1972 Woodenworks exhibit at the Renwick Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, DC, and the 1979 New Handmade Furniture exhibition organized by the American Craft Museum in New York. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The partners' task for the opening exhibition was to choose work from a multifacted, multi-centered field. By 1980, they had met Jere Osgood in Boston. His steering would be invaluable to the gallery since the studio furniture landscape was largely unlit at the time of the partners' research in the late 1970s. One of their most important discoveries, however, was closer to home. It was their future landlord, Leif Hope, without whose support and encouragement the partners acknowledge they surely would have had a more difficult road and possibly have failed. Tucked away on a back street in East Hampton, the 19th-century steam laundry building owned by Hope has been the gallery address for nearly 25 years. This location was perfect for the Johnsons because the stabilized rent not only made their expenses manageable, but also allowed an unhurried pace for them to develop an audience for studio furniture. One of their first acts as Pritam & Eames was to commission James Schriber to make an entrance door for the gallery. They reasoned that his padauk and aniline-dyed ash door would provide a clue from the outside as to what was inside. Good friends and owners of New York's Soho Charcuterie catered the gallery's opening on May 21, 1981. Many of the furniture makers came, providing enduring insight into their love of a good party. One of them said to a Fine Woodworking editor, "If any gallery is going to make it, it'll be this one." |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 9 8 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

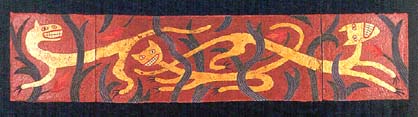

| Selections from the Opening Exhibition - 1981 | Opening Exhibition Judy Kensley McKie's work has much in common with the spirit-imbued carving of primitive cultures. Her images suggest energies beyond what you see. (See Notes, McKie l987 show). She was represented in the opening exhibit with a console table in the form of a pair of carved mahogany dogs supporting a glass top. She also showed a walnut blanket chest with carved bird and floral motifs in the facades, patterns that continue in her work today. Bill Keyser, on faculty at the School for American Craftsmen at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT), took his command of technique and applied it first to form and then to function. He was exceptional in the opening show in that he contributed a nonfunctional piece that was a wall sculpture made from long sections of walnut and cherry branches. He also showed a branched-formed clothes tree, that could stand alone as sculpture. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Judy

Kensley McKie - carved Walnut Bird and Fern Chest |

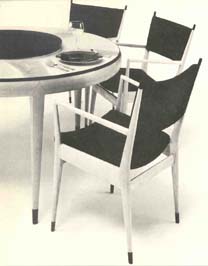

Wendell

Castle - Walnut and Elm Game Table, Chairs + |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Judy Kensley McKie - Mahogany Table with Dogs |

Alphonse Mattia - Red Lacquer Mirror Detail |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

William Keyser - Walnut Clothes Tree |

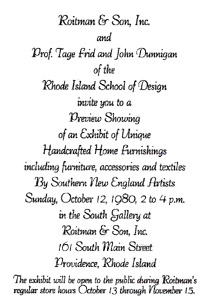

William Keyser - Maple and Walnut Split Branch Wall Sculpture |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rob Sperber - Walnut Thread Cabinet |

Hank Gilpin - Maple Bench Detail |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hank Gilpin - Oak Chest on Stand |

Hank Gilpin - Curly Maple Tea Cart |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Peter Korn - Cherry Dictionary Stand |

Peter Korn - Rocker |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

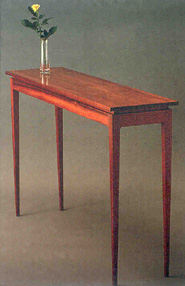

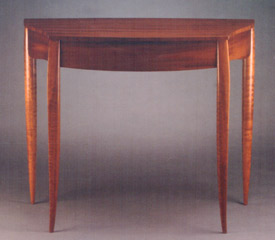

Timothy Philbrick - Rosewood Pier Table |

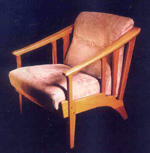

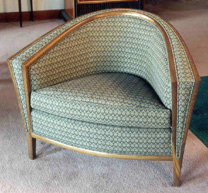

John Dunnigan- Walnut and Velvet Chair |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

John Dunnigan - Mahogany Table and Mirror |

David Ebner - Wishbone Oak Rocker |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Richard Newman - Mahogany Blanket Chest + |

Richard Newman - Black Limba Coffee Table Base |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bruce

Beeken - Bubinga Low Table |

Wendy Maruyama - Padauk Bench |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

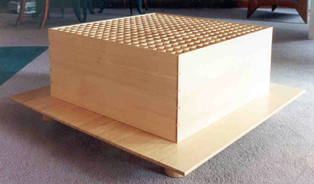

Thomas Hucker - Sitka Spruce Box |

Mark Lindquist - Maple Burl Bowl |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

George Gordon -Teak and Mahogany Sideboard

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 9 8 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

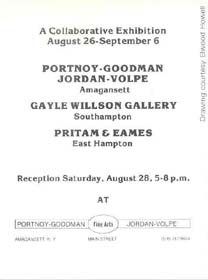

| Announcement

of 1982 Show Schedule |

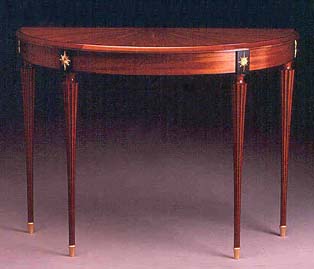

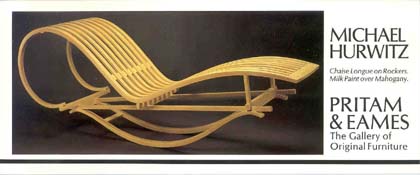

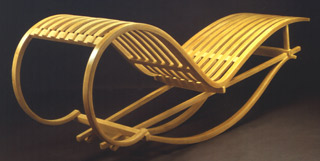

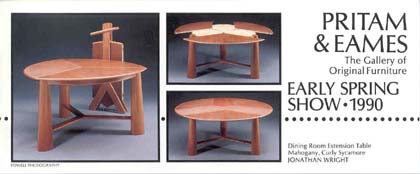

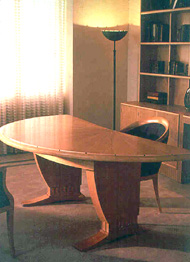

1982: New work from America's top designer-craftsmen Neal Barkon, Larry Bickford, Michael Coffey, Ron Curtis, David Ebner, David Ellsworth, Hank Gilpin, Michael Hurwitz, Hunter Kariher, William Keyser, Silas Kopf, Alan Lorn, Judy McKie, Charles Mark, Alan Marks, Richard Newman, Timothy Philbrick, Robert Sperber, Leslie Wells, Newell White, Jonathan Wright. NOTES: This show opened the gallery's second season. Seminal work from John Dunnigan and Richard Newman arrived this year. Newman's stunning dining table opened the 1982 season and Dunnigan's Versailles Table arrived for the Masters show later in the summer. These pieces established both makers as individual stylists from whom much could be expected. Richard Newman's dining room extension table in cherry, ebony, and ormolu broke radically with his past. A commission requested by his mother-in-law forced him to abandon his RIT Modernist style of work in favor of Louis XVI. Prior to working in the Modernist vein that he says was encouraged at RIT, Newman had made banjos. And it was the musical instrument making that prepared him for the fine decorative work that characterizes his furniture from here on. The dining room table combines cherry and ebony on the legs and apron, which also features cast gold-plated ormolu of androgynous faces set in relief. The table has a resawn, hand-planed top of figured cherry veneer. The effect of this combination is stunning, like nothing else in studio furniture at the time. Although the use of gold was anathema to some and considered elitist by others, Newman was mostly undisturbed. He said, "Gold is noble, it's a perfect material." When a piece sets a mark, it usually provokes some discussion. Work from others in the exhibit shows how well they, too, struck the vein of a successful personal furniture style. Such a piece is Tim Philbrick's pearwood and leather chair. The leather seat and back are tailored into an elegant pearwood frame, and outlined with red leather piping. Judy McKie's carved and painted plant stand shows her inimitable blend of animal and invented form. The skyward seeking thrust of the bird's head, wings, and legs is a gesture that communicates to everyone. With its fan-like form, the stylish padauk and purpleheart chest of drawers by Michael Hurwitz inverts the cabinetmaker's usual approach. In this case the largest drawer is on the top with the size of the drawers diminishing as they descend. David Ebner's English brown oak sofa table and chair demonstrate the strong impression that Wharton Esherick's style of work had on him. In the sofa table, he made use of a "poured leg" design for the first time: the top appears to continue and flow down into the leg form. You could dance on Gilpin's sassafras low table, affectionately dubbed a "foot stomper." It shows his fresh treatment of familiar form, as well as his preference for under-utilized domestic hardwoods. Some makers become associated with a single piece. Such was the case of Jonathan Wright's bubinga/maple dining room extension table. Without its leaves, the top is a deltoid or inflated triangle; with the addition of its three leaves, the top of the three-legged table becomes round. Wright would continue to make versions of this popular design into the 1990s. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature Pieces - Summer 1982 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

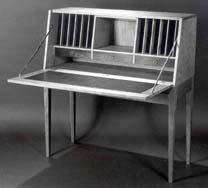

Alan

Lorn - Cherry Fallfront Desk |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Richard

Scott Newman - Cherry, Ebony and Gold Extension Dining Table + |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Richard

Newman - Cherry, Ebony, Gold and Silk Chair |

Richard

Newman - Details of Dining Table |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Michael

Hurwitz - Purpleheart and Padauk Chest of Drawers |

Judy

Kensley McKie - Bird Table + |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

David

Ebner - English Brown Oak Sofa Table and Chair |

Tim

Philbrick - Pearwood and Leather Chair + |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hank

Gilpin - Oak Foot Stomper Table |

Jonathan

Wright - Bubinga and Maple Extension Table |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Work

from the Masters - 1982 |

Work

from the Masters Wendell Castle, Michael Coffey, John Dunnigan, Wharton Esherick, Tage Frid, William Keyser, Sam Maloof, Alphonse Mattia, George Nakashima, Jere Osgood. Lecture by Wendell Castle, introduction by Jack Lenor Larsen. NOTES: This show paid tribute to those who helped shape the course of the studio furniture movement by their work and through their teaching. With the seven-year apprenticeship system a tradition of the past, the academic training centers on American campuses that developed in the 1960s and 1970s proved crucial to the development of the studio furniture movement. In addition to providing basic furniture making skills, these structured academic programs took place in an environment that ultimately fostered a freer, more dynamic approach to design. The schools also provided the opportunity for friendships and a spirit of camaraderie to develop between students and teachers which, in many cases, lasted long after graduation. At this point it might be helpful to give a sketch of some of the personalities in place at the time of the gallery's opening and to note the diversity of their background disciplines. Wharton Esherick's singular visionary authorship is generally acknowledged as the source of the American studio furniture movement. Trained in the fine arts in the early twentieth century, Esherick went from painting to woodcut printing, and then to sculpture and furniture in the 1920s. He received public notice when he collaborated with Philadelphia architect George Howe on a room setting for the 1939 World's Fair. Esherick's legacy was that he showed the possibility of using wood to create sculptural furniture forms. He was also instrumental in showing the way to use found objects, such as materials from the woods or even from one's backyard, in furniture. Self-taught, he was not bound to the use of a particular set of tools or techniques and advocated the use of anything that would get the job done. Esherick's 1965 cherry and red oak library ladder in this show was borrowed from the collection of Jack Lenor Larsen, an early avid Esherick collector. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wharton Esherick - Cherry Library Ladder |

George Nakashima - Walnut Conoid Chair |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sam

Maloof - Walnut Rocker |

Jere

Osgood - Maple Side Chair |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

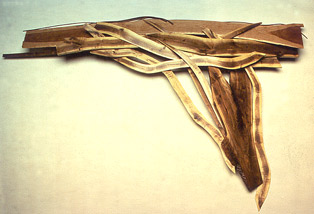

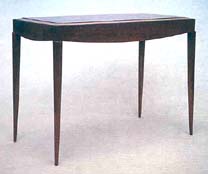

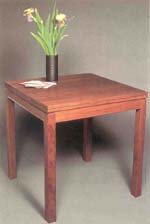

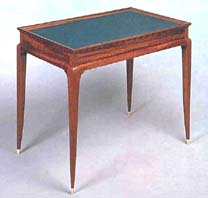

Tage Frid - Mahogany Flip-Top Game Table + |

Wendell Castle - Curly English Sycamore |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

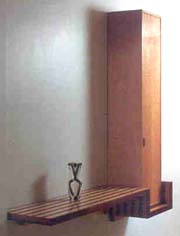

William

Keyser - Maple and Padauk Shelf Cabinet |

John Dunnigan - Wenge, Purpleheart, and Epoxy Resin Table |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Another important figure in the early stages of the studio furniture movement was George Nakashima. Trained as an architect, Nakashima turned to furniture as a form of building in which he could involve himself "from beginning to end." He was among the Japanese-Americans interred during World War II in a detainment center in Idaho. It was there that he learned how to use traditional Japanese hand tools. Upon his release, Nakashima moved to New Hope, PA, where he produced furniture emphasizing simple lines and a respect for wood. With his shrewd business sense, as well as his background in design and architecture, Nakashima's one-man shop soon expanded to include a dozen skilled craftsmen. By the time the partners met Nakashima in 1979, his philosophy and practice to preserve the splendor of wood by making objects of use had evolved to such an extent that he had a much larger public audience than most studio furniture makers would ever enjoy. As Edward Cooke observed in New American Furniture:The Second Generation of Studio Funituremakers (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, catalogue, 1989), "Esherick and Nakashima gained a foothold in the high-end furniture market after World War II primarily through their architectural connections, but their subsequent success was also closely linked to the emergence of the studio craft movement of the 1950s. In furniture, different aspects of this movement arose among the self-taught and within the educational system." George Nakashima did not work with galleries as he did not like middlemen, but he agreed to support the fledgling Pritam & Eames with one of his Conoid chairs, this one in Persian walnut. The 1950s also saw other self-taught woodworkers like Art Carpenter and Sam Maloof develop their interest in furniture design and construction into new careers. Sam Maloof's 1955 walnut rocker in the P&E show was borrowed from the American Craft Museum collection. Interestingly, it fell to Tage Frid, a Danish cabinetmaker trained in the traditional European apprenticeship system, to establish the first college-level programs in this country with a furniture major, first at Dartmouth College in l948 and then at RIT when the program moved there in 1950. His traditional approach to design and his exhortation to students "to design around construction" exerted a profound influence, as well as reaction, on those who studied with him. Frid's students included Jere Osgood, Dan Jackson, and Bill Keyser. Frid left RIT to establish the furniture program at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in 1962, where his emeritus influence continues today with former students Rosanne Somerson, John Dunnigan, and Alphonse Mattia on faculty. In the Masters show, Frid's contemporary take on the game table was based on a simple flip-and-twist mechanism. As with most of his work, the detailing itself was kept to a minimum. The solid stance of the table, its clean functionality, and its handsome material show how Frid continued to be influenced by a modernist approach. When Frid left RIT for RISD, he was replaced by Wendell Castle, with Bill Keyser as Castle's teaching assistant. If Frid represented traditional cabinetmaking skills as practiced abroad in a journeyman's life, then Castle was his antithesis. He was inspired more by what was going on in contemporary sculpture than by furniture. Trained as an industrial designer and sculptor, Castle created wood furniture during the sixties and seventies utilizing the same stack-laminated techniques favored by other contemporary sculptors. As a teacher, his approach was radically different from Frid's. Instead of "design around construction," it was "'bring out the sketchbooks." Castle began his own studio school in the early eighties in Scottsville, NY. He was represented in this show by his sycamore and ebony demilune, part of his "fine furniture" series first shown at the Alexander Milliken Gallery in New York the previous year. He would later eschew this body of work, which had been inspired by the French ébéniste Emile-Jacques Ruhlmann, as overly reliant on skill. Much of Castle's work came to P&E in the 1980s as a result of the partners' friendship with Castle's New York dealer, Alexander (Sandy) Milliken. Bill Keyser came from a family where technical know-how was second nature. When Castle left RIT in 1969, Keyser took over as head of the furniture program, where he remained until his retirement in 1997. Keyser's padauk and maple shelf and wall-hung cabinet is a piece defined in linear terms. By using laminations of woods in contrasting colors, the linear form gains rhythm. As with most of Keyser's work, this piece combines innovative process with a sculptor's sense of form. When Krenov left PIA abruptly in 1976, it fell to Jere Osgood, and Dan Jackson, to lead the program in Boston. Alphonse Mattia would succeed Jackson at PIA as Jackson's health deteriorated. Osgood and Mattia provided a decade of inspirational teaching at PIA from l976-l986. The wide crest rail of Osgood's 1978 curly maple chair in this show evokes the outstanding chair designs by Hans Wegner of Denmark. And, in fact, as a student, Osgood worked for a year in Denmark, although he did not train with Wegner. Osgood's body of work comes from a consideration of the lines found in nature's forms. This chair takes ergonomics as a starting point and arrives at a form that is strikingly organic and inviting. The comfortable seat, made of belt leather, avoids the visual bulk and technical fussiness of upholstery. This side chair is one of Osgood's three classic chair forms, the other two being his dining chair (see 10 x 16, 1991) and his easy chair (see P&E Editions, 1994). Alphonse Mattia studied with Dan Jackson at the Philadelphia College of Art (PCA) and then with Tage Frid at RISD in the seventies. He said that he wanted to make a series of objects that were related to function, but not ruled by it. He was represented in the Masters show by his red lacquer mirror from the year before, which would not sell until it was reintroduced at the gallery's tenth anniversary show. The business end of studio furniture depends on a relatively small group of buyers. Although these buyers represent considerable connoisseurship, few among them are willing to purchase pieces simply because of their excellence. In the world of fine arts, the case may be different -- it is not uncommon to keep prized paintings in storage. Studio furniture is collected primarily as a means towards an end -- a piece usually represents a fulfillment of a specific need. Time and again, pieces of exceptional quality remain unsold. These cases are often heartbreaking for the maker, as well as for the gallery. At the time of this show, John Dunnigan was RISD's principal instructor in furniture making. For the Masters show, he made a side table that referenced the same 18th-century French furniture period as Richard Newman's dining table seen earlier, but with more of an attitude. Both tables perch on versions of the spade foot, though Newman used gold-plated bronze, while Dunnigan used cast epoxy resin. The rose color of the epoxy, seen on the feet and the rim of the tabletop, stands boldly against, yet remains sympathetic to, the wenge legs and the purpleheart top. [This Dunnigan side table would be included in the 2003-04 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston exhibit, The Maker's Hand, American Studio Furniture, 1940-1990.] At the time, Michael Coffey had his own studio school in Poultney, VT, and was represented in the Masters show by a dressing table suite including a mirror and stool in mozambique. Although not represented in this show, the gallery would exhibit the work of David Powell, director of the Leeds Design Workshop, Easthampton, MA, the following year. After his brief stay at both RIT and PIA, James Krenov went west to northern California and formed the wood program at the College of the Redwoods in 1981. He was not represented in the Masters show, but would send his first work to the gallery the following year. His work, and that of his students, became an important source of furniture making talent for the gallery that continues today. The Masters show was meant to acquaint people who walked through the door with some of the seminal figures whose work originated the field of studio furniture. In actuality, it was the well priced work of the masters' students, the coming generation of furniture makers, that allowed the gallery to survive its critical first years. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Design Approach: Wendy Maruyama & Ed Zucca - 1982 | Furniture

Making: The Design Approach NOTES: The work of Wendy Maruyama and Ed Zucca was the subject of P&E's first featured show, and it provided an opportunity for the young gallery to showcase furniture as original artistic expression. However, the confidence of the collecting public had yet to match the experimentalism and exuberance of the work. Later, Maruyama said that she was embarrassed that none of her pieces sold from this, her first featured exhibit. A supportive marketplace had not yet been created by galleries for art-driven furniture. The expressive nature of Zucca's and Maruyama's furniture styles can be traced to their background influences as well as their circumstances. Maruyama graduated from San Diego State University in 1975 where she studied with woodworker/sculptor Larry Hunter, whose work would appear in the gallery in 1984. While still in San Diego, Maruyama saw the catalogue for Fantasy Furniture, a 1966 show that included work by Tommy Simpson and Wendell Castle at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in New York. This was furniture to which she could aspire. Having read about the work being done by Alphonse Mattia on the east coast, she enrolled at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) and spent a semester studying with him. She followed Mattia to PIA in 1976 when he began teaching there with Jere Osgood. After two years at PIA, Maruyama went on to earn an MFA from RIT. At the time of the P&E show, Maruyama was teaching along with Tom Hucker at the Appalachian Center for Crafts in Smithville, TN. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wendy

Maruyama - Primary Chairs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wendy

Maruyama- Mickey Mackintosh Chair |

Wendy

Maruyama - I-15 to Vegas |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ed

Zucca - Captain Video Table of Painted Basswood and Raku Ceramic Tiles by Kathy Yokum |

Ed

Zucca - UFO Light |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ed

Zucca - Flourescent Electric Table |

Ed

Zucca - Floor Standing Light with Red Fan |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ed Zucca maintained his studio in Putnam, CT. He had studied with Dan Jackson in the late 1960s at PCA, a period when Philadelphia was a dynamic center of innovative craft work. Zucca's interests in tinkering and building were already well established, and his work referenced a variety of influences from Art Deco, Egyptian, and pre-Columbian architecture, Shaker furniture, to American cars and gadgets of the 1950s, to space-age fantasy-fueled objects. Zucca's wall-mounted light took the form of a Twilight Zone flying saucer, and his sound-emitting sideboard whined when someone would pass by. His space-crafted work, was an adventurous and humorous take on studio furniture. However, it is always a question, when embedding a high degree of novelty in a substantial piece, whether the longevity of comment is at variance with the investment. Maruyama's puckish Mickey MacIntosh chair was paired with her three painted Primary Chairs, with plate-glass seats. Her work was, in part, influenced by what was going on in contemporary Italian design at the time, a colorful style that came to be known as Memphis. Maruyama's first work in neon, I-15 to Vegas, appeared in her P&E show, a lamp that also included colored marquetry. Her infamous Scribble Desk arrived at the gallery in 1983. Its appearance, together with Garry Bennett's Nail Cabinet, on the back cover of a 1980 Fine Woodworking magazine, fueled the gathering discussion as to whether work like this was furniture or something else. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The

Bowl, the Vase, and the Box - 1982 |

Turned

Work: The Bowl, the Vase, and the Box David Ellsworth, Silas Kopf, Ed Moulthrop, Philip Moulthrop, Richard Scott Newman, Del Stubbs. NOTES: This exhibit included the work of four turners and two furniture makers who contributed boxes. Of the turners, Ed Moulthrop enjoyed a national reputation, and David Ellsworth was steadily building one of his own. The highlight of the exhibition, though, was the small, almost paper-thin, manzanita vessels of Del Stubbs. Silas Kopf contributed boxes with floral marquetry patterns, and Richard Scott Newman again demonstrated his mastery with ebony and gold. One shallow lidded box of ebony has a contemporary feel to it, utilizing platinum as well as gold wire in its diagonally dashed pattern. The other ebony box has an inlaid mother-of-pearl image of Pegasus against an ebony night sky. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ed

Moulthrop - Turned Tulipwood Bowls |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Del

Stubbs - Manzanita Goblets |

David

Ellsworth - Turned Bowl |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Silas

Kopf - Boxes with Marquetry |

Richard

Newman - Ebony Lidded Boxes |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The

Desk and the Reading Chair - 1982 |

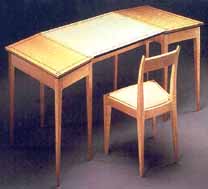

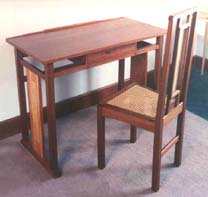

Reading

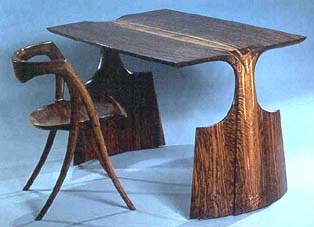

and Writing: The Desk and the Chair Lawrence Bickford, John Dodd, Tom Duffy, David Ebner, George Gordon, Peter Korn, Thomas Loeser, Ben Mack, Bruce McQuilken, Robert March, Alan Marks, Craig Marks, Michael Rosen, David Steckler. NOTES: Group shows are, by their nature, diverse in spirit. Nevertheless the serious observer will always come up with a few unprompted favorites, which gives these shows the excitement of the hunt. Thematically, of course, there can be some unifying concept such as, in this show, the desk. The gallery partners had received advice from design professionals that people would only be inclined to invest in pieces for the public areas of the home. The partners found, however, that a favorite piece for the collecting public was the desk, which normally would go into the private area of the home. Both the rosewood writing table with drawer by Craig Marks, and the padauk roll-top desk of Robert March, have unusually graceful lines that allow them to sit confidently in almost any interior. The line of March's tambour roll-top flows down from the carcase through the legs. There is also a great deal of flowing line in Marks' writing table, which was featured of the gallery's show announcement. Notice the similarity of the line in the legs of these two pieces, though the makers worked a continent apart. In Marks' table, however, the lines become the personality, set aggressively at 45 degrees into the apron. The carved pull is a signature of his teacher, James Krenov. Proving again the strengths of diverse training centers, Marks came from the College of the Redwoods, and March from RIT. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Craig

Marks - Rosewood, Kingwood and Ebony Writing Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Robert

March - Padauk Roll-Top Desk |

David

Ebner - Cherry Stand-Up Desk |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ben

Mack - Maple Desk |

Alan

Marks - Oak and Leather Easy Chair |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

John

Dodd - Cherry Desk |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stand-up or reference desks are not unique to studio furniture, but David Ebner's piece gave him a perfect format for showing off his poured leg design. The piece has a delicate but sculptural presence. John Dodd's desk in cherry focuses on pure line and is completely without ornamentation. Its design does not stem from any furniture tradition per se but is more in line with what one would expect from a contemporary architect. The curve on the front of the top contains pencil drawers and replies to the outward flare of the pedestal sides. It has a clean and inviting look. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Images

in Wood: Marquetry by Silas Kopf - 1982 |

Marquetry:

Images in Wood Silas Kopf Also new work from John Dunnigan, David Ellsworth, Richard Scott Newman, James Schriber, Del Stubbs. NOTES: Silas Kopf was established by 1982 as an expert in creative marquetry. He had apprenticed with Wendell Castle in the mid-70s, and continued occasionally to collaborate with him. Kopf employed craftsmen to build his pieces, which he would then use as a canvas for marquetry designs. In 1989, he studied with Pierre Ramond at the Ecole Boulle in Paris, further perfecting his mastery of marquetry. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

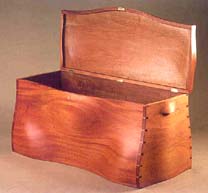

Silas

Kopf - Cherry Blanket Chest with Marquetryof Padauk, Bubinga,

Rosewood, Jacaranda and Holly |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Commissions

& Installations - 1982 |

Commissions

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

George Gordon - Set of Walnut Arbitration Tables for Manhattan Maritime Law Firm |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Home Office: David Ebner Chair; Hank Gilpin Walnut and Cherry Desk; Jim Fawcett Storage Cabinet in Pecan, Oak, Beech, and Tulipwood |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Two notable exceptions were the pioneering efforts of Patricia Conway, principal in the New York architectural design firm of Kohn, Pedersen, Fox and Conway, and David Schwarz, a Washington, DC, architect who worked with studio furniture makers on corporate as well as residential projects. Later, the partners surmised that there may have been a perception in the trade that studio furniture cost more, took longer, and did not offer customary trade discounts. From the furniture maker's side, working with an architect or designer in a commission situation often left the maker out of the design process. Makers ended up executing designs of others rather than their own. Some makers made a practical adjustment and built to specification as part of their production routine. Beyond that, the results of the commission process can be far from a surefire thing. It is fair to say that some furniture makers and clients ought not be placed together in a commission situation. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Summing Up:

The First Year's Lessons In the gallery's experience, clients generally make their own decisions and do not require professional vetting. They act as their own arbiters of taste, and for this a quotient of confidence is necessary. This fact does tend to limit the circle of collectors of studio furniture because it takes some strength to make such decisions. Whether a sales or commission situation, the client has to be convinced that the piece will work for them in an evironment that they know better than anyone else -- their own home. Jack Lenor Larsen has said you're not a collector unless you pay storage. But collectors of studio furniture are not generally of this nature. Their objective is to envision an acquisition that they will live with and use. You could argue that the challenge in placing studio furniture is more difficult than that of painting, not only because of the space furniture requires, but also because our tolerance of what is acceptable on someone's wall is greater than what we will accept to sit upon or eat from. The partners' mission was to show people that studio furniture was a real residential option, one that could heighten the quality of their lives in their most intimate surrounding. They didn't rely on pedestals to display work in the gallery. Rather, they assembled work in groupings that made synergistic sense, arranging pieces in familiar ways that suggested how they might look in a home. The natural eclecticism of studio furniture lent itself to some imaginative pairings. Group shows were the gallery's common exhibition format at the time, because the format served their mission very well. Many collections of studio furniture that began in the 1980s remain unequaled today. In Patricia Conway's book, Art for Everyday: The New Craft Movement, (New York. Clarkson Potter, 1990), she guides readers through the homes and offices of collectors and demonstrates how studio furniture works in living rooms, bedrooms, boardrooms, lobbies, offices, patios, and gardens. "These craft artists," Conway wrote, "are concerned not primarily with the expression of material and natural form as were their predecessors, these craft artists are direct descendants of the Arts and Crafts movement that shaped the early part of the 20th century. Their ethos is the unifying moral and aesthetic force of craft and the reconnection of that force with the everyday." The partners, who assisted Patricia Conway by introducing her to many of the collectors featured in her book, felt that Art for Everyday validated their approach. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 9 8 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spring 1983 | Spring

1983 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

James

Krenov - Maple and Red Oak Cabinet |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

James Krenov - Mahogany and Yaca-wood Cabinet + |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

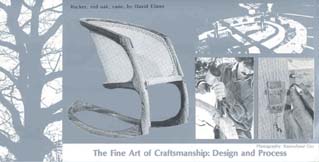

| The

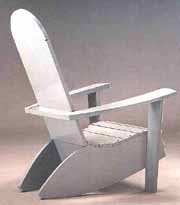

Fine Art of Craftsmanship: Design and Process - 1983 |

The

Fine Art of Craftsmanship - Design and Process Glenn Gordon's sturdy bench in lacewood is a compact composition of line and material. Although he would turn to writing in the future for creative outlet, this early small bench remains a strong piece. Bruce Beeken's cedar Adirondack Chair was the earliest piece shown at the gallery

to have been designed to be made in limited groups and marketed at a reasonable

price. It took a discerning eye, nonetheless, to appreciate the differences

between this chair and what was readily available in catalogues. The gallery

itself would begin its effort to market an edition series in 1995; and by

2001, Beeken himself would be ready to launch his own line of

Vermont furniture. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

John

Dunnigan - Pupleheart and Lacquer Table + |

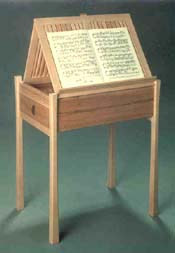

Wendell

Castle - Purpleheart and Maple Music Stand + |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Michael Hurwitz - Cherry and Lacquer Coffee Table |

Michael Hurwitz - Child's Chair |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

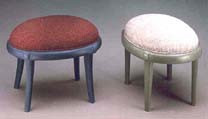

Tage

Frid - Walnut Stools |

William

Keyser - Pecan Low Table |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

David Ebner - Purpleheart Renwick Stool |

Glen Gordon - Ronchamps Bench |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bruce Beeken - Cedar Adirondack Chair |

James Schriber - Padauk and Ebony Game Table |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

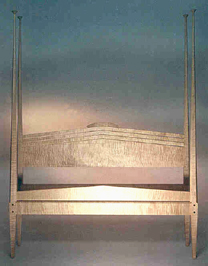

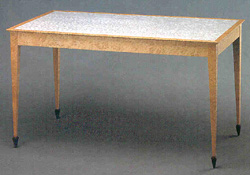

James

Schriber - Ebonized Maple Table |

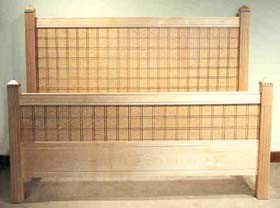

James Schriber - Ash Bed |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Included in this show were three pieces by James Schriber. The stylistic differences between the black table and the queen-size ash bed are such that one would not assume that the same person designed both pieces. This versatility and design fluency has distinguished Schriber's work throughout his career, and also makes him among the most commissionable of furniture makers. Schriber played an exceptional role in studio furniture as he gave the wider public more faith in the field. The black table, has a slick contemporary elegance, while the ash bed harks back to Carl Malmsten and Schriber's time with Osgood at PIA. "Country" is the word that comes to mind to describe the bed, and "urban" the table. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

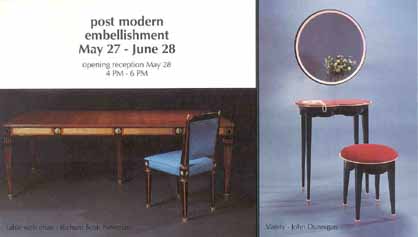

| Post-Modern Embellishment - 1983 |

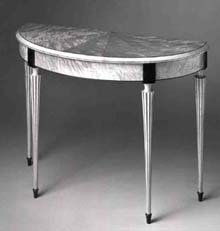

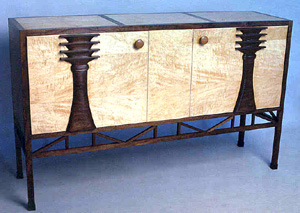

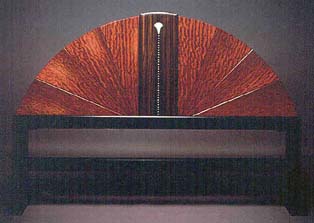

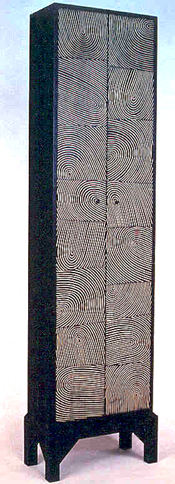

Post-Modern Embellishment - 1983 Dale Broholm, John Dunnigan, Alphonse Mattia, Judy Kensley McKie, Richard Scott Newman, James Schriber. NOTES: This show focused on the decorated surface, and the use of paint, epoxy resin, gold, ebony, and carving. Patricia Conway observed that Post-Modernism was regarded as a reaction against the austerity of Modern design, and its exclusion of ornament. Since the early 1970s, a number of furniture makers, architects, and designers renewed their interest in pattern and decoration and the application of pure ornament to furniture, rooms, and buildings. "The universal appeal of ornament is precisely its 'uselessness'," Conway writes in Ornamentalism: The New Decorativeness in Architecture and Design, co-authored with Robert Jensen (Clarkson Potter Inc., 1982). "Because ornament does not hold things up or make things work, it is essentially free: free to move the eye, to intrigue the mind, to rest the soul; free simply to delight." The epoxy resin in John Dunnigan's Vanity Suite (shown on the announcement) and the ebony detailing in Richard Scott Newman's demilunes exemplify the theme of this show. Newman exhibited a pair of demilunes, one in cherry and ebony, the other in maple and ebony. These original demilunes presaged the slightly larger versions of the table that would become his signature piece over the next ten years. Later, a commission allowed Newman to design a ten-foot wide version of the table (pictured under Commissions, 1989). In studio furniture at this point, two pieces came to symbolize a movement in the field that took decorative detailing into the realm of art ideologies. One such piece was Garry Knox Bennett's padauk cabinet with a 16-penny nail pounded into one beautifully crafted door. This act on Bennett's part certainly would have been in keeping with the Dada movement. Many assumed that Wendy Maruyama's Scribble Desk that appeared in this exhibition derived from the same spirit. But, according to Maruyama, this is not true. Her intention was to embellish the top surface of the desk with a calligraphic gesture rendered in as free a manner as possible. She used a crayon, then lacquered the surface. Both Bennett and Maruyama's pieces appeared on the back cover of Fine Woodworking in 1980, to the consternation of some who thought they were desecrating the wood. Ed Zucca's Egyptian Dynasty Cabinet is an apt example of ornamentation. The nature of its façade is entirely determined by two bold, but strange, tower-like bas-relief figures on the front. This piece was made before his space furniture series. The Egyptian-style work, although distinctive and appealing, was not a style to which he would return. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| + rsn table | + reverse slide | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

John

Dunnigan - Purpleheart and Marble Table |

Richard

Newman - Maple and Ebony, First Demilune |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wendy

Maruyama - Scribble Desk |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ed

Zucca - Egyptian Dynasty Cabinet |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Alphonse Mattia - "Fragile" Mirror |

Alphonse Mattia - "Unbreakable" Mirror |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Judy

Kensley McKie - Carved Birch Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dale Broholm - Lacewood, Pearlized-Paint Upholstered Chair |

Dale Broholm - Cabinet |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Both Fragile and Unbreakable are part of a signature series of mirrors by Alphonse Mattia that would represent him well in the gallery world until the appearance of his valet series in 1984. Remarkable work from Judy McKie surfaced again in this show. Her table exhibits the first use of the lizard-like form, to which she would return in the future. The creature is carved into the leg material and its upward motion takes the eye in a continuous sweep up to the braided pattern of the apron. This table is a precursor to her Grinning Beast Table that she made for a 1986 P&E show. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

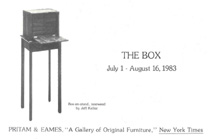

| The

Box - 1983 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Del

Stubbs - Cocobolo Lidded Containers |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Jeff

Kellar - Rosewood Box-on-Stand |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature Pieces: The Desk for Home & Office - 1983 |

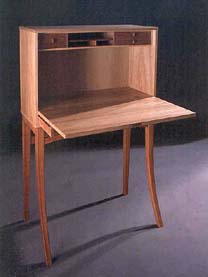

Signature

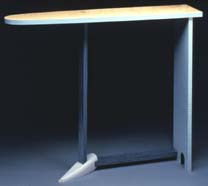

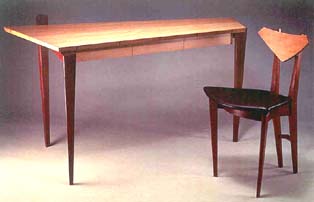

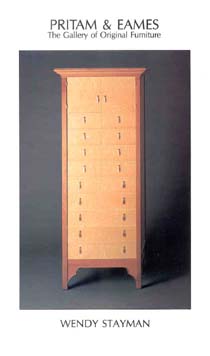

Pieces: The Desk for Home & Office Wendell Castle, Michael Coffey, John Dodd, John Dunnigan, David Ebner, Hank Gilpin, George Gordon, David Hannah, Creighton Hoke, Silas Kopf, Peter Korn, Alan Lorn, Benjamin Mack, Robert March, Wendy Maruyama, Jere Osgood, David Powell, Wendy Stayman, John Tierney, Stewart Wurtz, Robert Whitley. NOTES: Listed in this show are desks by Wendell Castle, Jere Osgood, and David Powell. The Castle desk uses his by-now familiar pinwheel leg-to-apron design with maple parquetry running up the legs and along the apron top to frame a green leather writing surface. One of Castle's simplest decorative treatments, and the desk is strong because of it. David Powell, like Castle, was responsible at that time for a studio school, Leeds Design Workshop in Easthampton, MA. Powell had been trained by Edward Barnsley of the English studio furniture movement, but his desk owes more to the experimental forms of the 1960s than to Arts and Crafts influence. The carcase of Powell's desk is egg-shaped in profile and upholstered in leather. The Barnsley-Powell connection was an important trans-Atlantic association; another was that of the British furniture maker John Makepeace and Wendell Castle. Jere Osgood made only a few pieces in the early 1980s. He has acknowledged that it was very difficult to do his own work while running the PIA program, especially during the first years of its existence. It would take until 1985 before he was able to create enough work for a two-person show with his former student, Tom Hucker. In this show, the surface of Osgood's simple walnut and ash writing table is supported by a curved leg structure built using his tapered-laminate technique. The asymmetrical design of the forward and rear legs allows the top to cantilever from a central pedestal. Freed from the traditional "leg at the corners" design, the top takes on an aerodynamic quality. Basic to Osgood's thinking is the idea that forms expressing a natural flow of energy will never simply be linear. Of note is a fall-front desk by Wendy Stayman, whose name was appearing on a gallery listing for the first time. Trained at Wendell Castle's studio school, her fall-front desk in pearwood and maple exhibits both the architectural crispness associated with her work as well as her knowledgeable eye for decorative detail. The pear and maple combination is a visual feast. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wendy

Stayman - Pearwood, Holly, Maple and Leather Fall-front Desk |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wendell

Castle - Walnut, Curly Maple and Leather Writing Desk and Chair |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

David Powell - Personal Desk |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Jere Osgood - Walnut and Ash Desk |

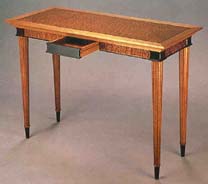

John Dunnigan - Maple, 24K Gold over Bronze Writing Table |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Commissions - 1983 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Peter

Resnick - Art Nouveau Silver Chest |

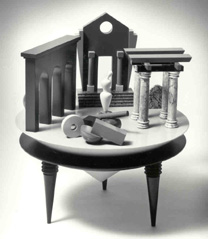

Ed

Zucca - Space Suite |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

George

Gordon - Walnut Dining Table |

Jonathan

Wright -One of several small Bubinga conference tables for a Philadelphia

law firm |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The

Discreet Object of Desire - 1983 - 1984 |

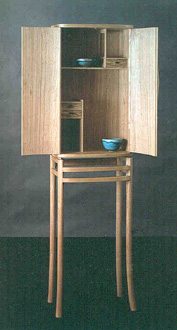

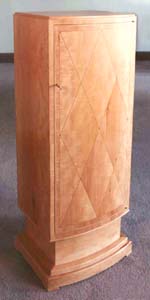

The

Discreet Object of Desire Wendell Castle, John Dodd, John Dunnigan, David Ellsworth, Hank Gilpin, George Gordon, Reg Herndon, Michelle Holzapfel, Thomas Hucker, Michael Hurwitz, Silas Kopf, Ben Mack, Charles Mark, Richard Scott Newman, Zivko Radenkov, Del Stubbs. NOTES: The appearance of work by Reg Herndon and Zivko Radenkov signified the onset of influence that graduates from Krenov's program at The College of the Redwoods would have on P&E exhibitions. The impact of Zivko Radenkov's spare and reverential Winter Cabinet is even more pronounced when set against the strong decorative styles that were prevalent on the east coast at the time. Here, it is the reserve of the decorative element that makes its mark. The slender bare branches tell us the season and the remaining leaf completes the composition. Radenkov says of this cabinet that he "wanted a wintry sort of feeling with still a few leaves hanging around before a breeze carries them to the cold ground. In the lower corner of the right panel, there is a falling leaf being carried off by a small swirl of wind. I used the western curly maple for background to convey the sense of a cold winter day. So, all in all, the cabinet is a fantasy of looking out some window and you see what you see." Radenkov would continue into the 1990s to produce cabinets decorated with marquetry patterns of floral motifs. This exhibit also marked the arrival of work by Michelle Holzapfel. She would continue to exhibit her turned and carved pieces at P&E until the early 1990s. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Zivko

Radenkov - Winter Cabinet + |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

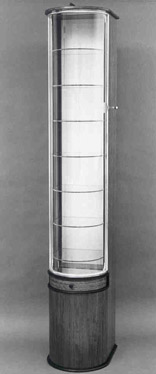

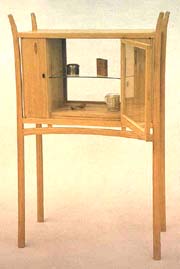

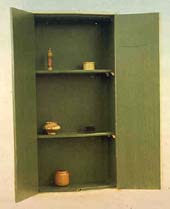

Reg Herndon - Maple Display Cabinet |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Michelle Holzapfel - Cherry Burl Beet |

Michelle Holzapfel - Turned and Carved Pumpkin |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

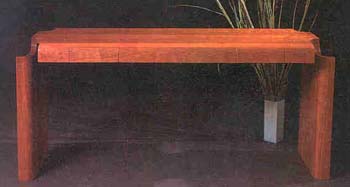

Silas Kopf - Mahogany and Narra Coffee Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 9 8 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

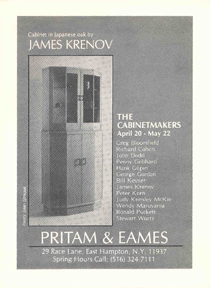

| The

Cabinetmakers - 1984 |

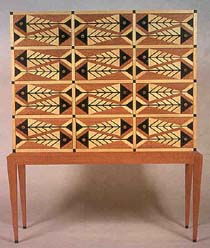

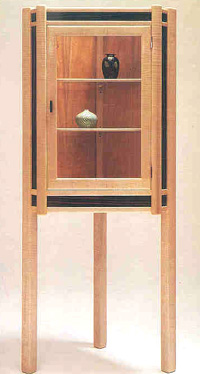

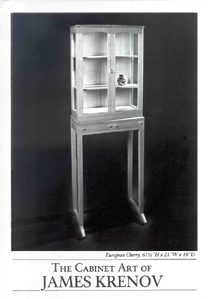

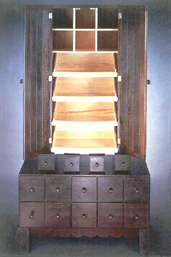

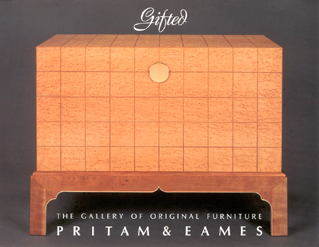

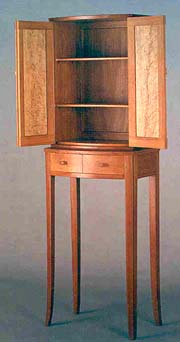

The

Cabinetmakers Greg Bloomfield, Richard Cohen, John Dodd, John Dunnigan, David Ebner, Penny Gebhard, Hank Gilpin, George Gordon, Bill Keyser, Silas Kopf, Peter Korn, James Krenov, Tom Loeser, Ben Mack, Charles Mark, Alan Marks, Wendy Maruyama, Judy Kensley McKie, Richard Newman, Ronald Puckett, Stewart Wurtz. NOTES: The Krenov cabinet pictured on the announcement is only 57 inches high and 26 inches wide. At the time, it marked a still-rare appearance of his work in the United States. This cabinet, in Japanese white oak, is related to one that he made in Sweden 15 years earlier. The 1984 piece is composed of a small showcase attached to a larger base cabinet, which is raised by a plinth. Krenov previously had used a functional base cabinet to support a hip-high section, but he would not return to a closed base form for 10 years. Perhaps he felt that he said it perfectly with this cabinet. Everyone, especially his students at the time, remembers this piece. The small black/white image on the show announcement sold the cabinet over the phone to someone who knew nothing about Krenov or studio furniture. It remains one of his purest pieces and one, regrettably, that he does not repeat. The Cabinetmakers show included the Fish Cabinet by Judy McKie, her largest case piece to date. The cabinet form, a perfect horizontal rectangle, provided her with an ample canvas for starkly angular fish imagery, which are repeated across the front in a geometric pattern. The table base lifts the case much like an aquarium. McKie would return periodically to the large case piece as a means to explore pattern and two-dimensional designs. She returns to large surface-pattern exploration in her 1995 Pattern Table, this time on a horizontal surface. Gilpin's minimalist fumed white oak cabinet has a certain monumentality for its size -- chest height. The illusion is enhanced by its unusual plinth base. The minimalist sense of the piece is reinforced by its single front door. The cabinet's warm tone was achieved by fuming the oak with ammonia, a 19th-century French technique. David Ebner's Lingerie Chest marks the first appearance of this piece at the gallery, but not the last. It follows the French formula of seven drawers, one for each day of the week. Its anthropomorphic form a robed figure, giving this piece its signature. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

James

Krenov - Japanese Oak and Glass Cabinet |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Judy

Kensley McKie - Fish Cabinet |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hank Gilpin- Fumed Oak Cabinet |

David

Ebner - Mahogany Lingerie Chest |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

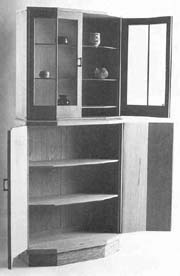

Greg Bloomfield - Bubinga, Ebony, Glass and Silver Showcase Cabinet |

George

Gordon - Corner Cabinet |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

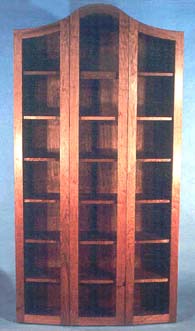

Peter

Korn - Cherry Breakfront |

Silas

Kopf - Walnut and Marquetry Breakfront |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

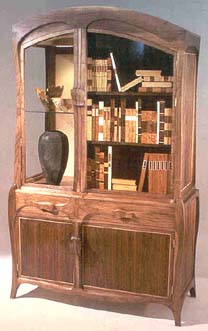

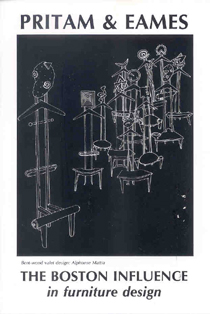

| The

Boston Influence - 1984 |

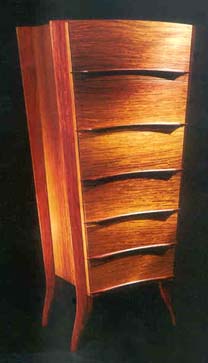

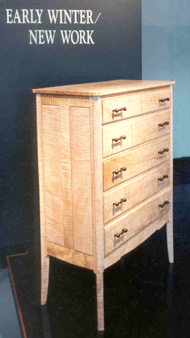

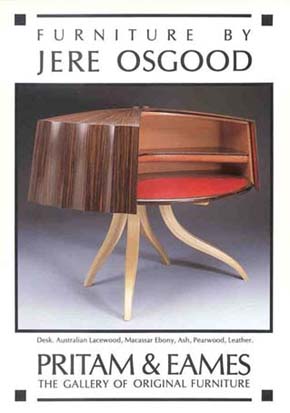

The Boston

Influence The appearance of Jere Osgood’s padauk and ebony Chest of Drawers in this show was a precursor to a regular contribution of major pieces from this outstanding maker. Although Osgood had developed his thinking about chests in the 1970s, the investment of time in a piece such as this five drawer chest makes their appearance rare amongst Osgood’s speculative pieces. The next chest of drawers, his three drawer low chest, would not show at the gallery until ’95. And his tall or lingerie chest would not appear until 2003. Visually, the striking feature of these chests is their curved torso-like shaping. The width of the chest is narrower at the bottom with deeper drawers. The drawers get shallower as they widen towards the top. The curve of the front also becomes more accentuated as the piece progresses upward. This chest literally swells as in the tension of skin over muscle or the viscosity of a drop. This is accomplished by curving both horizontally and vertically. Although you see compound curving in other Osgood pieces, it is most effective in these chests. To accomplish this visual simplicity, the drawer fronts are all different bent laminate constructions. The sides of the chest which also swell vertically are coopered from shaped solid staves. The stems of the pulls are through tenons and pinned with wedges on the inside. The solid top is dovetailed into the sides. For a look at an earlier Osgood chest, see the one included on page 58 in the catalogue for the 2003 exhibit at the Boston MFA, The Maker’s Hand – American Studio Furniture, 1940-1990. Although Judy Kensley McKie and Rosanne Somerson attended RISD and not PIA, their inclusion in this show reflects their influence and proximity to the Boston makers. PIA graduates not represented in this show but whose work also is associated with P&E include Bruce Beeken, Tim Philbrick, and James Schriber. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Alphonse

Mattia - Valets |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

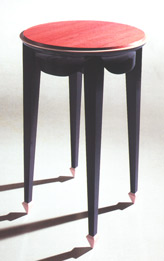

Side Tables - Dale Broholm |

Wendy Maruyama - Drawers with Pointy Legs |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Thomas Hucker - Beefwood and Linen Bench |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tom Loeser - Oak Side Chair |

Tom Loeser - Painted Maple "Mouse Hole" Table |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Michael Hurwitz - Tall Cherry Table |

Mitch Ryerson - Beefwood, Ebony, Walnut, Maple "People" Chair |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Michael Hurwitz - Brandy Vault |

Michael Pierschalla - English Brown Oak, Black Lacquer, Leather Writing Desk |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Judy Kensley McKie - Butternut Jungle Chairs with Oak Table commissioned from John Dunnigan |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rosanne Somerson - Painted Mirror |

Jere

Osgood - Andaman Paduak Chest of Drawers |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

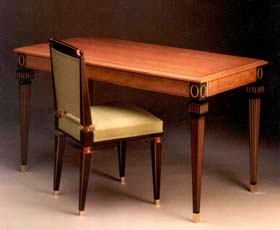

Stewart

Wurtz - Swiss Pearwood and Purpleheart Writing Table and Chair |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

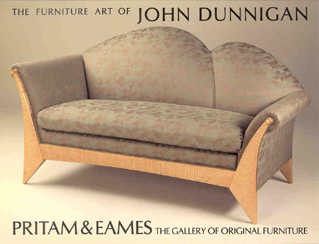

| Two Furniture Makers: The Re-Emergence of a Tradition - 1984 | Two

Furniture Makers: The Re-Emergence of a Tradition John Dunnigan, Richard Scott Newman. NOTES: This was the second exhibit that featured individual makers. Here the notion that a furniture maker can create a signature body of work as original as any painter takes on weight. Richard Newman was trained at RIT and had worked for Wendell Castle; John Dunnigan, trained at RISD, studied with the legendary Tage Frid. As part of the exhibit, both lectured at the Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, NY and at PRITAM & EAMES. John Dunnigan's high-style vanity is sumptuous in its use of material and color. The curly maple top was set up by a base painted in a red as definite as that used in Chinese furniture. The neoclassical leg refers to Egyptian bundled papyrus, a metaphor that Dunnigan would use again. The design of Richard Newman's umbrella stand also used the bound bundle metaphor. This time the structure is actually made by joining of curved staves. These elements were not staves in the usual sense, they were complex laminations that allow the compounding of the curve. The elements that joined the staves were surfaced in ebony, adding a heightened sense of depth, structure, and material richness. Although the form itself was attractive and unusual, on close inspection it was the beaded bronze banding that made you catch your breath. The braided beads were individually cast and gold plated, and set into an ebony bracelet. A perfectly fitted, interior-blackened copper canister fulfilled the piece's functional promise. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

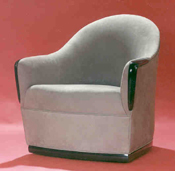

John Dunnigan - Ebonized Mahogany Boudoir Chair |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Richard

Newman - Umbrella Stand |

John

Dunnigan - Maple, Red Lacquer Vanity Suite |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| An

Exhibition of Desks and Chairs - 1984 |

An Exhibition

of Desks and Chairs |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stewart

Wurtz - Pearwood, Ebony and Lacquer Desk |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wendell

Castle - Lady's Writing Desk with Silver Inlay |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Richard Newman - Carving fluted feet for Pearwood Chairs on a Bridgeport mill |

Richard Scott Newman - Pearwood Chairs |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Robert

March - Hickory Desk |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

William Walker - European Cherry Writing Desk and Two Chairs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Creighton

Hoke - Pearwood Fall-Front Desk |

Ben

Mack - Maple Desk and Chair |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

David

Ebner - English Brown Oak Desk Suite |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

John

Tierney - Maple and Lacquer Chair |

West

Lowe - Pudding Mahogany Leisure Desk |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Commissions

- 1984 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Michael

Coffey Walnut Pedestal Table and Charles Marks Chairs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hank

Gilpin - Cherry Trestle Table, Fumed Oak Cabinet; Hans Wegner - Chairs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

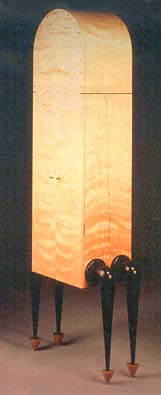

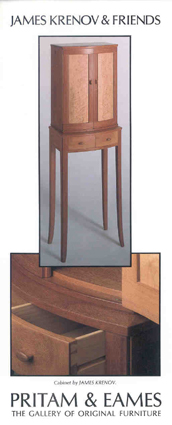

| James

Krenov & New Works - 1984-85 |

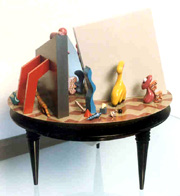

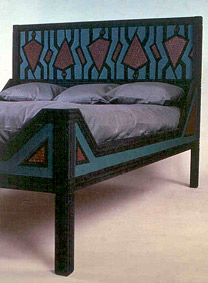

The

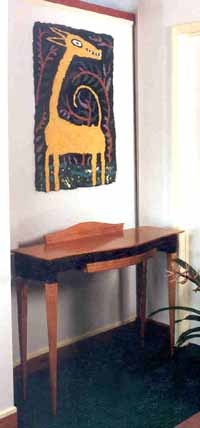

Cabinet Art of James Krenov & New Works Judy McKie's Dog Eat Dog table was a forerunner of many tables she would do over the years in which she would use paired animal forms.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

James

Krenov - European Cherry and Maple Cabinet, and European Chestnut Cabinet |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Michelle Holzapfel - Yellow Birch Burl Ram's Horn Vase |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Michelle Holzapfel - Ash MFK Fisher Bowl |

Michelle Holzapfel - Breakfast in Bed |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

William Walker - White Oak Chest |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hank Gilpin - Maple and Walnut Chairs |

Bob March - Rosewood Dining Table |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hank Gilpin - Ash and Fumed Oak Keyhole Chairs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

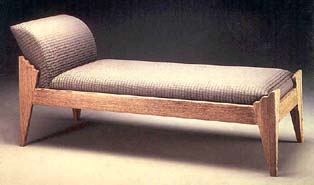

Timothy

Philbrick - Curly Maple and Silk Chaise Longue

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

James Schriber - Purpleheart Table |

John Dunnigan - Exclamation Point Chair |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

James Schriber - bleached Maple, Pink Ivory and Satinwood Bed |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lawrence Hunter - Walnut and Birch Clock V-2 |

David Ebner - Red Oak Scallion Coat Rack |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Judy

McKie - Dog Eat Dog Coffee Table- Carved Limewood, Milk Paint and Glass |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 9 8 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

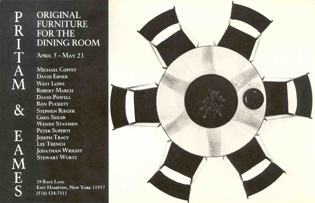

| Original

Furniture for the Dining Room - 1985 |

Original

Furniture for the Dining Room |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

David

Powell - Maple, Ebony and Granite Dining Table & Chairs

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wendy Stayman - Satinwood and Maple Silver Chest |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ron Puckett - Paduak and Copper China Cabinet |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Judy

Kensley McKie - Carved Limewood Abstract Chest |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bill

Keyser - White Oak Dining Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

David

Ebner - Rosewood and Maple Stick Table |

Peter

Superti - Wenge, Satinwood, Africa Bean Pods and Fiber Tropical Rain

Cabinet |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Joe Tracy - Maple and Plexiglass Tea Cart |

Robert

March - Rosewood Harvest Table |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Michael Coffey - Mozambique and Glass Dining Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

John Dunnigan - Dining Chair |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Jonathan

Wright - Maple and Pearwood Dining Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Original

Furniture for the Living Room - 1985 |

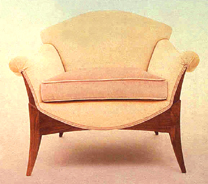

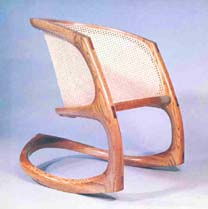

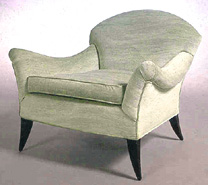

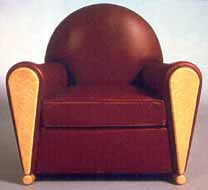

Original

Furniture for the Living Room Dale Broholm, Michael Coffey, Peter Dean, John Dodd, John Dunnigan, David Ebner, Hank Gilpin, Thomas Hucker, James Krenov, Silas Kopf, Ben Mack, Robert March, John Marcoux, Richard Scott Newman, Tim Philbrick, Ron Puckett, Stephen Rieger, James Sagui, James Schriber, Rosanne Somerson, Lee Trench, William Walker, Robert Whitley. NOTES: The participants in this show demonstrated the strength of four centers of studio furniture study in the mid-1980s: RIT, PIA, RISD, and the College of the Redwoods as represented by James Krenov himself. This exhibit reflected a group of makers in full stride. The upholstered form is one species of studio furniture which brings the best work from some makers, and which others never touch. Upholstered chairs, settees, and sofas benefit most from a relationship with a talented upholsterer. This takes trust, patience, and serious out-of-pocket expense. Nevertheless, the successful pieces are rewarding for both maker and client since so little refined work is available commercially. Early shows exhibited the upholstered work by John Dunnigan and Tim Philbrick, and both would continue to excel at this form. Upholstered work from James Schriber would appear in future shows. In this show, Stephen Reiger introduced his upholstered Easy Chair. It was remarkable for the degree to which he utilized the chair's exposed wood to give the upholstered form a crisp and stylish appearance. The chair is very comfortable. David Ebner's settee and easy chair have the presence of smoothly sculpted volumes. Where Reiger's exposed wood makes you aware of the formal properties of his chairs, Ebner's work exposes less wood and uses it as embellishment. Its roundedness suggests ultra comfort, though both chair and settee are actually compact, space-conservative forms. Also of note from Reiger was his oak floor lamp styled as a neo-classical column. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

David

Ebner - Lounge Chair |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Spadone-Rieger

- Upholstered Chair and Oak Lamp; David Ebner - Upholstered Settee Richard Newman - Maple and Ebony Demilune |

Joe

Tracy - Teak, Silk, Granite Rock Lamp |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Judy

McKie - Carved Limewood Bird Cabinet with Marble Top |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stephen

Rieger - White Oak Column Lamp |

John

Dunnigan - Maple, Ebony and Leather Desk, Handpainted Silk Chair |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

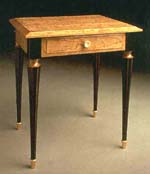

James

Schriber - Padauk and Leather Game Table

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Robert

Whitley - Walnut Rocker |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

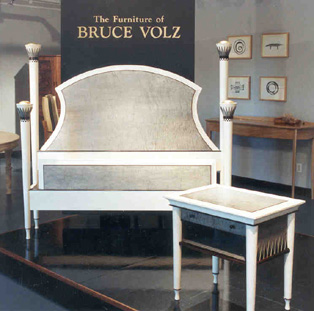

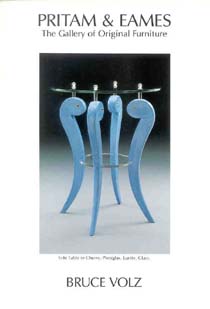

Bruce

Volz - Ebonized Walnut and Holly Side Table |

Dale

Broholm - Curly Birch, Ebony, Leather-wrapped Legs Highboy |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Silas

Kopf - Maple Marquetry Wine Cabinet |

James

Sagui - East Indian Rosewood Powder Cabinet |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

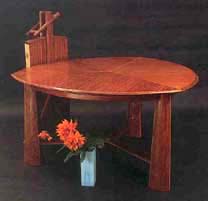

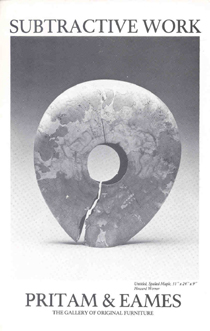

| Subtractive Work - 1985 | Subtractive

Work Jon Brooks, David Holzapfel, Howard Werner. NOTES: This exhibit focused on work made by reducing a large chunk of wood to reveal form, rather than achieving form by joining smaller pieces of wood. At the time of this show, Wendell Castle, one of the pioneers of carved forms made from stacked solids, had abandoned this method of construction. He would return to the subtractive process in the 1990s with his Angel Chairs series exhibited at the Peter Joseph Gallery in New York. Both Jon Brooks and Howard Werner work with monolithic blocks of wood and continue to produce vital bodies of work that demonstrate this enduring dimension of studio furniture. Howard Werner met Jon Brooks in the 1970s at RIT and was influenced by his approach of carving solid wood with the chain saw. Refined form and chain sawing would seem to be mutually exclusive concepts; however, sculptors had long been drawn to this technique for rapid removal of material. In this show, Werner's work demonstrated a sculptural sophistication. His five-pointed star dining table shows how far he had stretched chain-saw technique in order to render a complex form. Other pieces in this show were only nominally furniture-related and his vessel or dish-forms essentially cross the line into non-functional work. From its beginning, the gallery was decidedly in the functional corner of the studio furniture movement, but the partners certainly recognized that a good piece of furniture might have some things in common with sculpture. Both Howard Werner and Jon Brooks move freely between pieces that may or may not function as furniture. In Werner's case, he acknowledges that he was heavily influenced by such sculptors as Isamu Noguchi and Constantin Brancusi, as well as by the primitive carving techniques of Africa and Oceania. The underlying point here is that although Werner moves freely between functional and sculptural pieces, his work springs from the discipline of studio furniture, not from sculpture. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Howard

Werner - Elm Sphere |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Howard

Werner - Standing Maple Dish |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Howard Werner

- Walnut Dish |

Howard Werner

- Curly Maple Star Dining Table |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Jon

Brooks - Walnut, Red Oak, Brass Palenque and Night Lighting |

Jon

Brooks - Tasmanian Blackwood and Myrtle Music Stand |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

David

Holzapfel - Butternut Hollow Table Base |

Like Werner, Jon Brooks' low table treads the line between sculpture and function. Early in his career, he focused on found organic form as a primary element in his work. Brooks credits his artist-in-residency at the University of Tasmania in 1983-84 as a turning point in his work because he moved from single carved timbers to constructed sticks and color. Work from Brooks will often include colored pencil, acrylic, and pastels on wood. In this show, his combination of branch forms and saw-tooth cut-outs created a witty, animated form for a music stand. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

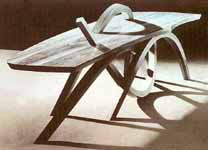

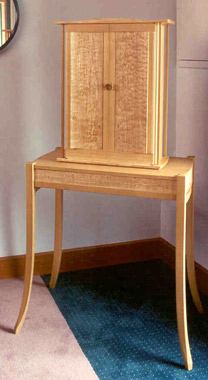

| Furniture

of Thomas Hucker & Jere Osgood - 1985 |

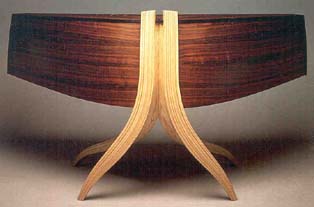

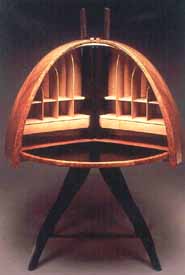

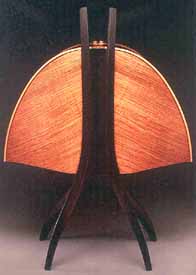

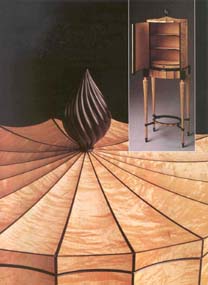

The

Furniture of Jere Osgood & Thomas Hucker NOTES: This show attests to former student/teacher influences that are still discernible in technique and form. This early featured show introduced pieces by both Tom Hucker and Jere Osgood that will be considered classic in their life's body of work, notably Hucker's low table on bronze pedestals, his slatted and cantilevered low table, and Osgood's rosewood and ash desk with legs that spread like a strong root structure and an aerodynamic spread-winged carcase suspended from its trunk. Osgood's sweeping cantilevered pedestal desk with its open upper cabinet took center space in this exhibit. Made of Brazilian rosewood and ash, this desk assumes visual command. What remains singular it is the horizontal stretch of its open cabinet. Osgood basically takes his flying wing tabletop and its cantilevered pedestal base and builds the cabinet as a shell structure shaped by the rear curve of the writing surface. The shell itself curves upward with the line of the pedestal posts. But the plane of the shell acts as a visual multiplier of the energy of that rear curve. The user, facing the interior of the shell, can select from a balcony of shallow drawers that stretch the entire width. Osgood's second shell desk for the show was the first of his dome-shaped shells: shells constructed from curved, wedge-shaped segments, tapering to a central axis at the top. These desks open from side-to-side, the doors revolving back around the stand. Here is a true interior space that the user can close entirely for privacy. As a result, the interior takes on a special character. Osgood sets up the interior space by his choice of pearwood and the suspended curved drawer and partition structure that is not built up from the table's surface. In this shell desk, as with later versions, Osgood's construction of the interior shelves and drawers have evolved to articulate miniature architectural spaces with their own architectural integrity. See, for example, his 2001 Shell Desk. The interior of this Dome Desk reflects the architecture of the whole. As in the rosewood desk, the suspended drawer structure allows the writing surface to extend to the rear of the piece without interruption. What chair to use with a desk like the Brazilian rosewood Shell? Osgood offers a solution with his curly maple chair. Its signature wide crest rail, reminiscent of Carl Malmsten, gives the kind of horizontal sweep that is comfortable with this desk. If there could be a piece as distinctive as the Brazilian rosewood desk but still hold its own, it would be Tom Hucker's slatted low table. Designed for a sofa or easy chair, it suggests a tatami-sized room and a community of rice bowls as Hucker's love of Japanese culture bubbles through. His focus was foremost to create a large table surface with transparency that avoids glass. The cantilever structure of the slatted table shows Hucker's emulation of his teacher, Osgood. Somewhat overshadowed by the slatted table, Hucker's other low table springs from earlier bench forms: it is narrow, stretched long, and structurally evokes a palanquin. The ends in this case are cast bronze stands. From end view, they could be Brancusi torsos. Here, however, they relate strongly to the Shield Chairs included in this show. This low table, a signature Hucker piece in the coming years, will be seen later with bronze stands and a verdigris patina, as well as in stone. The use of linen cord as a decorative element is a tactile contrast to the hard bronze. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Jere

Osgood - Rosewood and Ash Desk |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Jere Osgood

- Bubinga and Wenge Dome Desk |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Thomas Hucker - Walnut, Ash and Linen Slatted Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Thomas Hucker

- Beefwood and Bronze Low Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Profile

of Hucker Low Table |

Thomas Hucker

- Lacewood and Partridgewood Sofa Table |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Thomas Hucker

- Lacquer and Wenge Side Board |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Thomas Hucker - Lacquer and Wenge Shield Chairs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Shield Chair redefines how a chair can be. It trades familiarity for conceptual challenge. Structurally it accomplishes the engineering required by any chair -- countering the racking forces created by being seated. It is architecturally interesting as well, especially in the way its shape defines an interior space. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Commissions

- 1985 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Richard

Scott Newman - Cherry, Ebony and Vermeil Lady's Writing Table and

Chair |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Richard

Scott Newman - Curly Maple, Ebony and Vermeil Bench |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

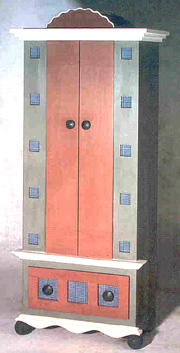

James

Schriber - Padauk Bedroom Suite |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

James

Schriber - Wenge Armoire of Bedroom Suite |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Objects

on a Smaller Scale - 1986 |

Objects on a Smaller Scale |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hap

Sakwa - "Before Dawn" |

Hap

Sakwa |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Silas

Kopf - Clock |

Michelle

Holzapfel - "Continental Breakfast" |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 9 8 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 27

Race Lane Opening - 1986 |

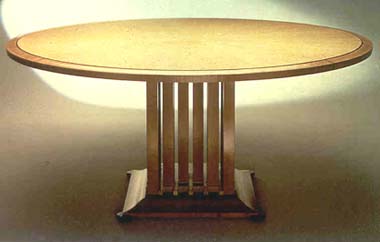

Gallery