|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

© Copyright 2009 Pritam & Eames |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

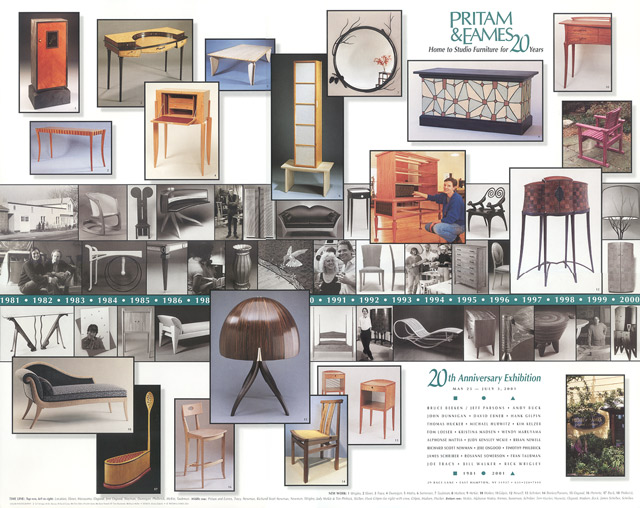

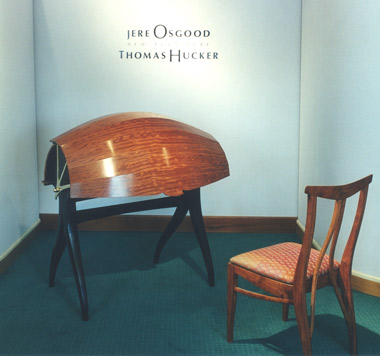

Pritam & Eames: The Second Decade 1991 - 2001 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Traditionally, furniture was built to satisfy a practical or ceremonial need. It was claimed beforehand: it was bespoken. "Studio furniture," a term coined to describe the work of the mostly college-trained makers of the second half of the 20th-century in this country, includes speculative work -- that is, furniture that no one has requested or specifically needs. The emergence of speculative work was fueled, in part, by the idea that furniture, like art, can be expressive of its maker. It should come as no surprise that the cross-fertilization of ideas that a university environment fosters would inevitably give substance to the revolution brewing within traditional crafts. Craft mediums like glass, clay, and fiber seemed to absorb the functional and non-functional duality of their nature easily. However, because of its historical ties to use, furniture was probably the last of the craft disciplines to embrace the non-functional compact with contemporary art. In a 1991 New York Times article, Witold Rybczynski asks, "If a Chair is a Work of Art, Can You Still Sit on It?":

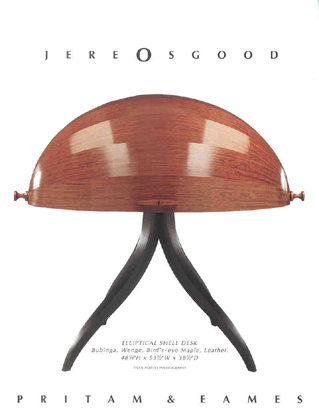

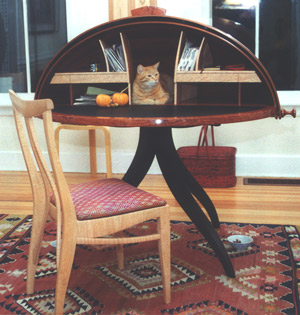

These issues would play out in the 1980s as university-trained makers challenged the orthodoxy of wood, conventional methods of construction, and the axiom that the crafting of the object was more meaningful than the concept or idea behind it. In the 1960s and 1970s, while Wendell Castle’s stacked, carved, subtractive forms brought the attitude of a sculptor to furniture, process innovations like Jere Osgood’s pioneering work in tapered laminations and compound shell constructions, or Bill Keyser’s innovative vacuum bag pressed forms, or Richard Newman’s sophisticated shaping jigs, provoked their own creative breakthroughs. The 1990s underscored this dual creative channeling -- part sculptural, part process-driven -- as furniture making was stretched against the background dichotomy of function versus art. In order for the spec makers to realize their artistic goals, a gallery system was needed to present, promote, and market their work. It would take time to develop this new marketplace, but by the mid-1980s there were signs of its early strength. Also, it can be said that studio furniture benefited from the post-modernist movement of the times because that decorative arts vogue provided a broader context in which to place it. As one furniture maker notes, “We were almost fashionable in the '80s.” In the 1990s, the saga of studio furniture unfolded with the emergence of New York galleries that sought to have furniture accepted on the same terms as fine art. It would be fair to say that the partners’ representation of furniture as furniture was, to some degree, overshadowed by what went on in New York during the halcyon art-boom days of the 1990s. High-end gallery marketing can bring its own pressure on the kind of work that gets made. This, in turn, can encourage makers to create pieces visualized for a gallery setting rather than furniture’s traditional context, the home. The ultimate divorce between furniture and its historical milieu takes place, however, when the museum enters the picture. By 1990, inclusion in curated/invitational museum exhibits was sufficiently seductive that few furniture makers questioned the appropriateness of new furniture making its first appearance in a museum. Museum exhibits produce lists, and these lists -- whose name is on and whose name is not -- become powerful operatives in the marketplace. Now that the museum has entered the marketplace, a new concept can emerge -- furniture bespoken by the museum, and offered for sale. The sine qua non for success in the craft world appears to include the same roster that dominates the fine-arts world: the museum, curator, patron, dealer, and artist. The auction house will be added to this list shortly. Rybczynski observes:

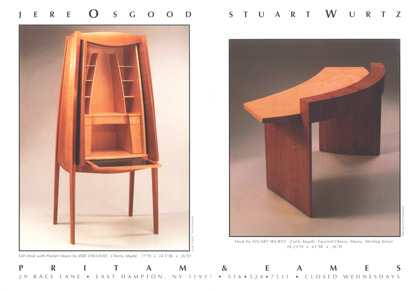

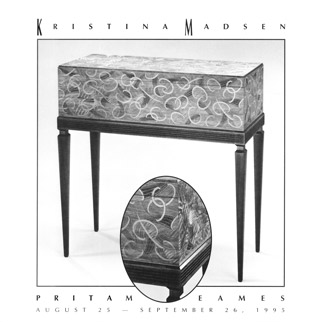

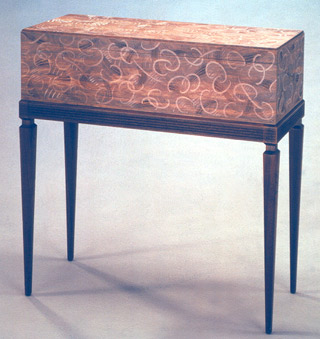

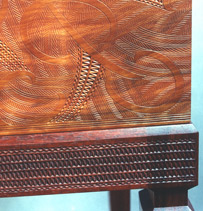

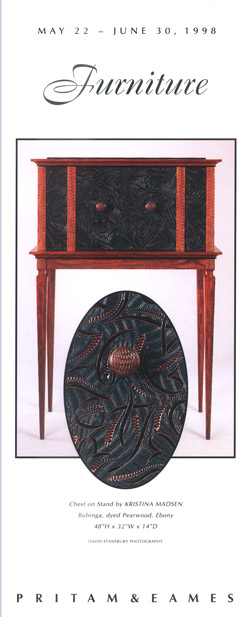

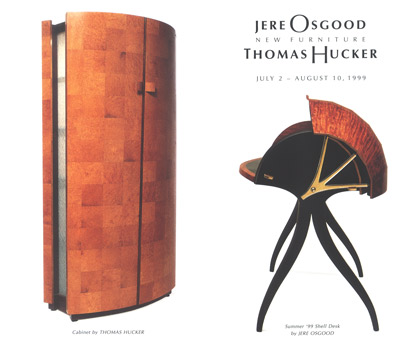

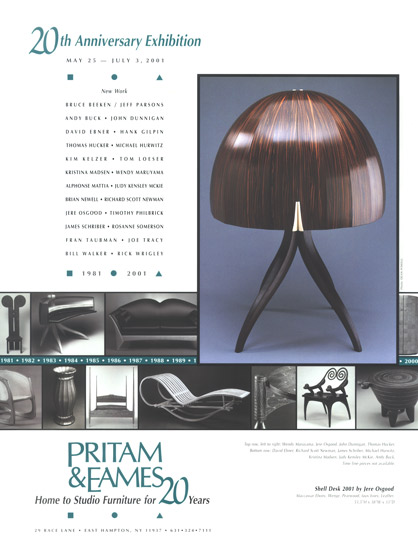

As some furniture makers aspired to be called artists, some artists lamented what they sensed was their loss. In 2005, Art Spiegelman, artist and writer, observed that the two biggest changes in the last 50 years in art have been the proliferation of museums of contemporary art and art fairs, and budget travel. “This means,” he says, “that more and more artists make works that they never expect will be lived with, looked at day-in and day-out by the same person; that much art is made for fairs or museums, designed to grab a distracted passerby's attention without needing to be experienced twice." Thus, he says, "culture slides into the realm of entertainment.” Until recently, furniture had avoided this unenviable outcome because of its close ties to the home. It is difficult for the partners to talk about the 1990s without talking about Peter Joseph, their client of nearly ten years. In November 1989, at the Quilted Giraffe Restaurant in New York City, Joseph proposed that the partners join him to create a New York gallery. Initially, the three discussed a partnership, but it became clear that their views for the direction of this gallery were divergent. The partners stepped aside, and Peter Joseph opened his Fifth Avenue gallery in New York in 1991. Many eyes were trained on this event. For those on the roster, as well as for those who wanted to be, this gallery venture seemed like a long-awaited validation of their artistic worth. In an important sense, the next moment in studio furniture’s dialectic was played out within the white walls, hardwood floors, and fine arts setting of this urban gallery. There, the work of some makers looked at ease, while others seemed out of place. The Peter Joseph Gallery contracts with makers required world-wide exclusivity. In return, the gallery provided promotion of their work through featured shows, along with catered openings, and color catalogues. This is the art-gallery prototype. By its own terms, this artist-to-gallery relationship required productivity, and the exclusivity of the arrangement required support for the makers. This led to a system of stipends. In order to attract a new clientele, the gallery offered a regular change of shows. The amount of work produced for these shows, however, was ahead of the market, which led, in turn, to a surplus of unsold pieces. The surplus of unsold work led eventually to a practice of serious discounting. It also left a serious question: when a design is constant, productivity is the key. But if the key is creativity, how does the pressure of productivity affect the outcome? Ultimately, the expensive gallery catalogues and commissioned testimonials from academicians and intellectuals like Arthur Danto and Witold Rybczynski notwithstanding, the Peter Joseph Gallery failed to secure the imprimatur of an art establishment. The art world seemed largely indifferent and even hostile to the idea of studio furniture as a 20th-century art form. When the New York gallery closed in 1996, it seemed to underscore the dubious practice of marketing furniture like fine art. An effort, observes Tom Hucker, akin “to trying to bake a chocolate cake with no chocolate. No matter how long you mix it, you ain't gonna get a chocolate cake.” After he closed his gallery and before his death in 1998, Joseph returned to Pritam & Eames as a client. Setting aside differences in their approach to marketing and recent history, he said he wanted to work together and publish the book of interviews begun by the Johnsons in 1989; a project he joined as co-editor in 1992. Sadly, he died before the project was realized. Some questions linger from this period. How does the perception of value get shaped? What makes one artistic pursuit more valuable, viz., remunerative, than another? What makes a chair by Scott Burton, the sculptor, more valuable than a chair by Jere Osgood, a master furniture maker? And who, ultimately, will determine the value of studio furniture: the galleries, collectors, museums, historians, critics, or auction houses? Throughout the 1990s, Pritam & Eames continued its mix of group, featured, and one-person shows. It also initiated the P&E Editions series. By this time, the furniture makers associated with the gallery had evolved distinctive, well-defined styles in their work, which they continue to refine throughout the 1990s. Explosively new and original work by two furniture makers emerged during this period: Kristina Madsen in the mid-1990s and Brian Newell at the end of the decade. By 2001, Pritam & Eames felt fortunate to have been in place for over 20 years, to have hosted a consistently high level of studio work and, also, to have been the beneficiary of a loyal and discerning public. If a Chair Is a Work of Art, Can You Still Sit on It? by Witold Rybczynski. DESIGN VIEW; The New York Times, May 5, 1991. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1 9 9 1 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

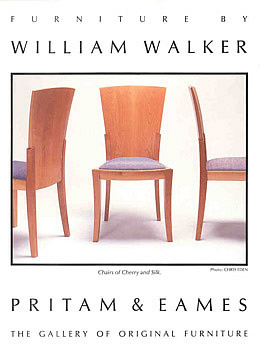

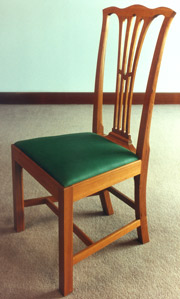

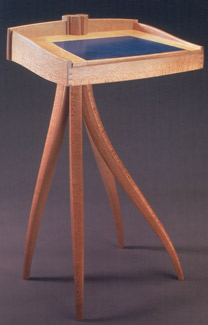

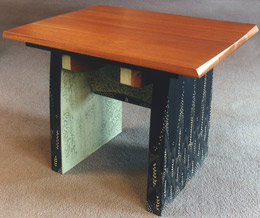

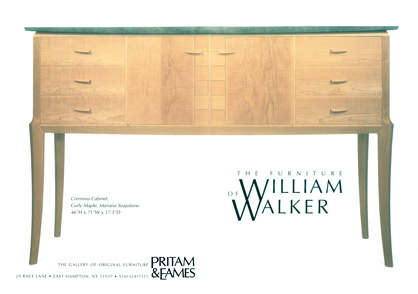

| Furniture by William Walker - 1991 |

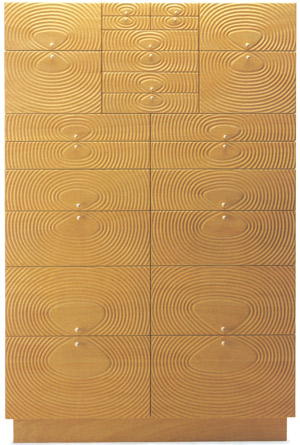

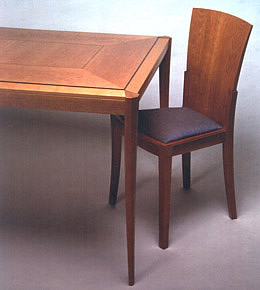

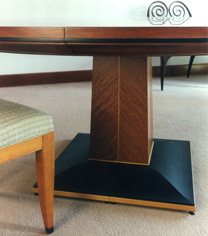

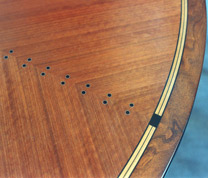

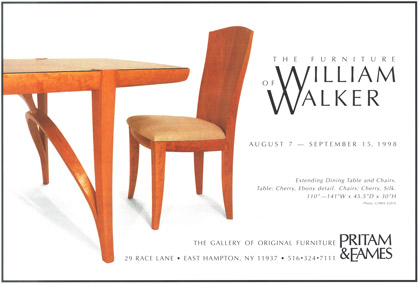

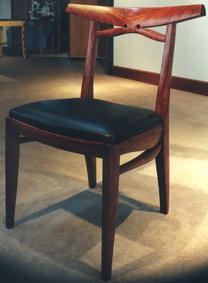

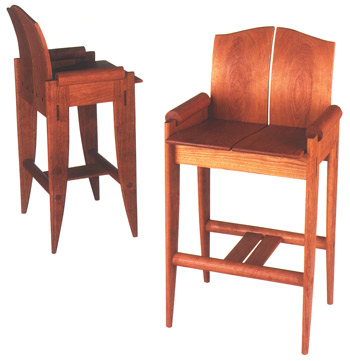

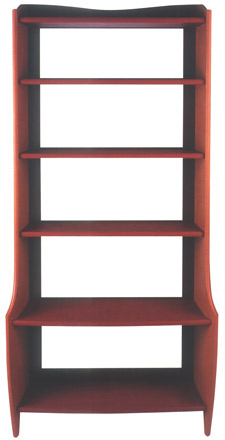

Furniture by William Walker Absent, though, to any considerable extent in this Walker work is an obvious reference to his mentor, James Krenov. In fact, the curved and aerodynamic quality of his side table and his solid fan-backed dining chair seems more in line with the thinking of the Finnish-born architect/designer, Eero Saarinen, or even Jere Osgood. Still, Walker's maple Silver Cabinet does reflect Krenov's attention to material as a major source of inspiration. The centerpiece of scale for this exhibit was Walker’s first dining room extension table. He called his previous table, shown at the gallery in 1987, a breakfast table. This time the table is a fully-fledged dining table with a set of eight chairs. And with this piece, Walker joins a small group of studio furniture makers willing to speculate on a piece of this scale. Richard Newman and James Schriber did so in the gallery's first decade and, although George Gordon, John Dunnigan, and Ron Puckett also made extension tables during this period, they did so on a commissioned basis. Walker's table establishes certain features that he will continue to use in future dining tables. Each one will have beautifully decorated surface created by sequential band-saw cuts of unusually thick veneer. The advantage of this veneer process is that it allows the best use of the most beautiful wood but, by being unusually thick, (1/8”), it also provides opportunity to refinish a daily used surface without fear of going through a delicate veneer. The second feature of this table is that the top is not just supported by four legs, but the legs are set into the top in such a way that they establish a dramatic design character for the entire table. By joining the legs at 45-degrees to the apron sides, they seem to stand proud of the apron and define the projection or extension of the table itself. This impression is augmented by their interesting shaping. Three forward facets create the surface that project out and into the room. The leg, itself, intersects with the table's apron with two larger facets which themselves join to define a corner of the eating surface. The part of the leg that faces towards the table’s interior is completed with a rounded section. At cross section, this is a complex shape. The three flat surfaces are flat only in their width, as these faces travel down the leg to its foot, the leg has a gentle saber curve. The crisp intersection of these facades is one of the table’s tailored features. The downward curved surface of the apron supports and reinforces the curves found in the legs. With unusual perception, Walker combines the tailored aspect of precise intersections with the flowing and biomorphic quality of his curves. The apron also gives the top a dimension of depth and solidity. The top of the table presents a dining surface with a difference: the apron that joins the legs has a flat top surface several inches wide that gently cants away from the eating surface. This is a friendly invitation to rest the diner’s arm. The dining surface itself is raised slightly proud of this apron surface and is defined by an ebony line. A band of veneer further defines the dining surface within the ebony line with grain pattern running from table edge to center suggesting the area for flatware. These bands are mitered at the corners and pleasantly suggest the diagonal projection of the legs. A narrow rectangle of veneer surface is left to the inside. The third feature of this extension table that Walker will continue to use in future dining tables is its wood extension mechanism. Despite the inherent strength of steel mechanisms, this wood feature universally pleased gallery visitors. There is something about the pleasure of secret treasure when a feature of quality is hidden within. Eight chairs accompany the table. In the solid wood fan-back dining chair, you can see Walker looking back at Eero Saarinen. This, however, is no Arts and Crafts-era chair, but a fully conceived contemporary design that would appear on the cover of Fine Woodworking later this year. To be comfortable, the coopered solid back was not only curved around the back, but also fitted to the incline of the spine and shoulders. It is kept as a simple unbroken form that joins into an upward extension of the rear legs. The legs themselves reference the dining table, as do their aprons. The upholstered seat sits into the chair’s frame, upping the difficulty of the process considerably over the use of an overlapping upholstered form. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cherry & Ebony Dining Table & Chairs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cherry & Ebony Dining Table & Chairs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

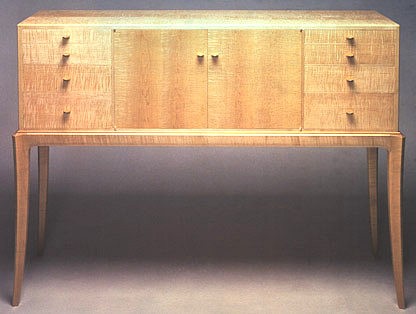

Cherry Chair & Bubinga, Maple Sideboard |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bubinga, Maple Sideboard + |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

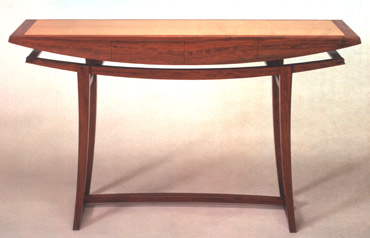

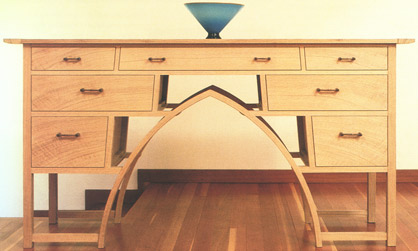

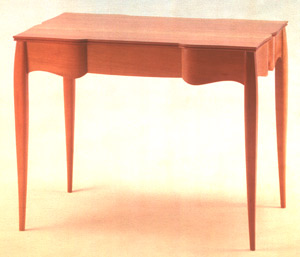

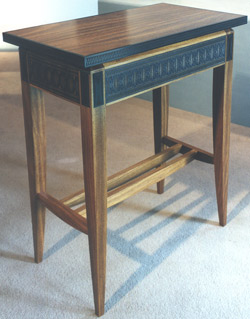

Writing Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

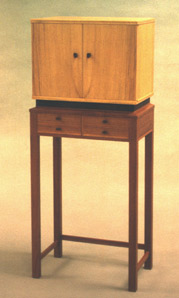

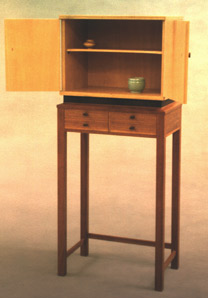

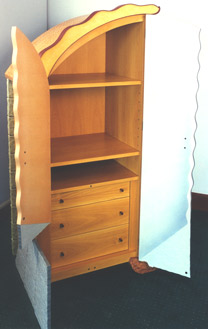

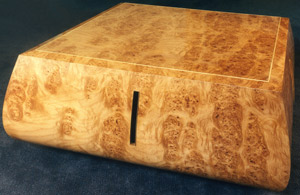

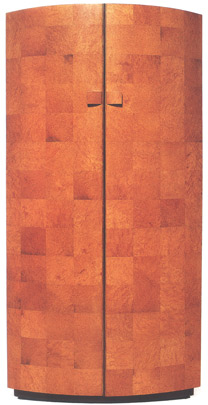

Eastern & Swedish Maple Silver Cabinet |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Every accomplished maker creates work that comes to be seen as his or her signature piece. For Walker, the bubinga sideboard or console is one such piece, and one well remembered by gallery visitors. Within Walker’s body of work, it is unusually sculptural. The boat shaped volume of its top has less to do with functionality, although it does house two narrow drawers, and has more to do with form: in this case, a streamlined and water borne volume floating serenely above its supporting table base. The curve of the rail of this table base strengthens the form, suggesting surface tension and buoyancy. The same curve is nicely reversed to add visual tension in the lower stretcher, which runs lengthwise between the legs. This piece again reflects more the quality of Saarinen’s work and less traditional table architecture. The single tonal drama is produced by a maple veneer rectangle that is centered on the top. Walker’s Silver Cabinet or sideboard was another candidate to steal the show. In this piece, he looks back to his 1987 sideboard in ash that set the theme for his affection for long, chest-high cabinets that sit on a delicate, elegant table base and whose legs seem improbable supports for the cabinet mass they carry. In the 1987 piece, Walker used a double horizontal stretcher at the top of the legs to create structure with no lower leg stretchers. Here, too, he follows this formula of simple, uncluttered elegance where everything depends on the joinery at the legs’ top for the piece’s stability. Like the dining table, the sideboard's legs are set in at 45-degrees. The front is composed of two central doors, flanked by two sets of four shallow drawers. The drawers graduate in size and become narrow in depth as they approach the top. Beyond this, the visual pleasure of the front of the cabinet is left entirely to the use of figured re-sawn maple which, like the earlier ash cabinet, flows horizontally across the drawer fronts, but vertically on the doors. This stark pattern is striking, and is enhanced further by its utter simplicity. Also, the use of re-sawn figured maple reflects Krenov’s attention to material as a major source of inspiration. There is more ample space for serving pieces beyond the doors. Narrow drawers are also included in the bottom of this space; not surprisingly, their width is asymmetrical, a sure Krenov touch. Over the years, there will be two more of these cabinet/sideboards to come from Walker’s shop to the gallery. It is interesting to study the different design solutions he employs in each cabinet to visually integrate the line of the leg into the bottom of the cabinet. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

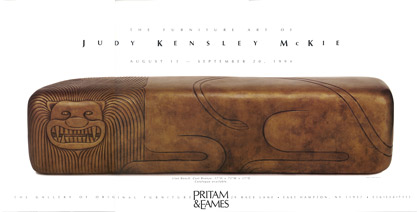

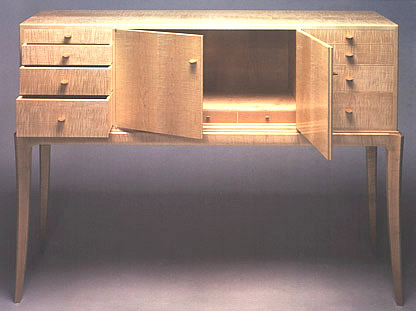

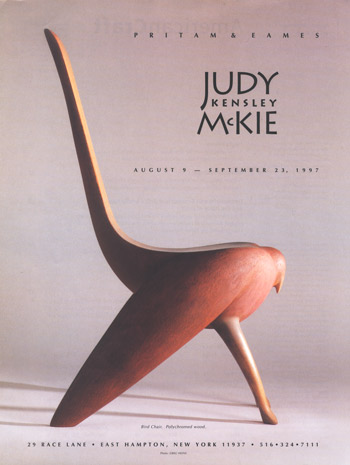

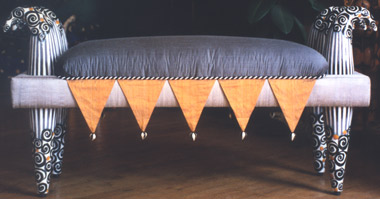

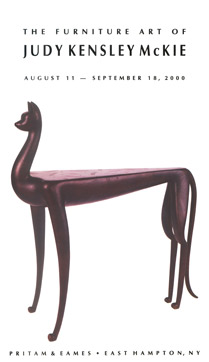

Judy Kensley McKie - 1991 |

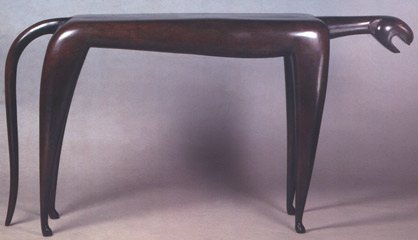

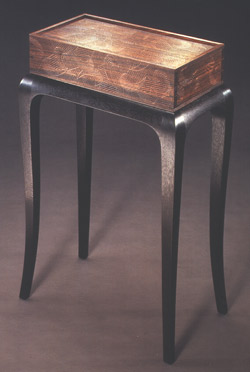

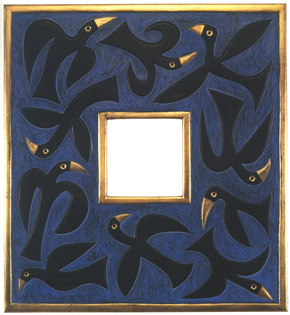

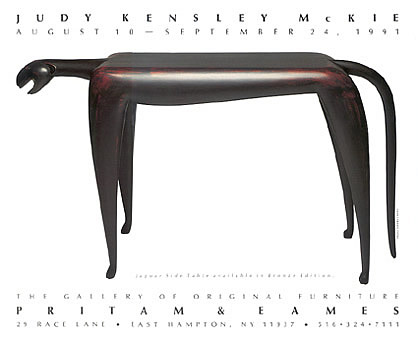

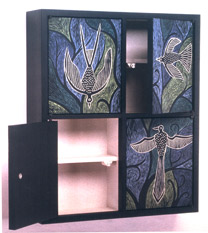

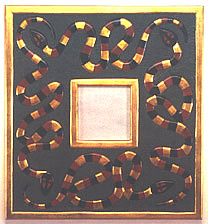

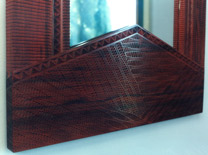

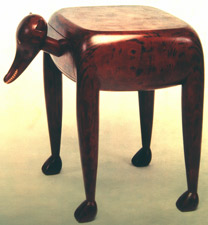

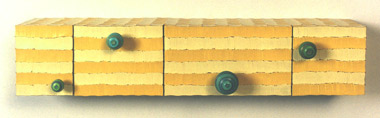

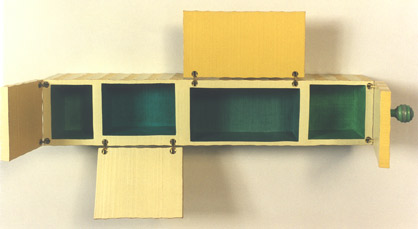

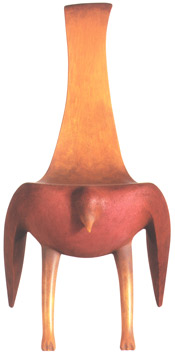

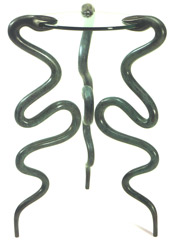

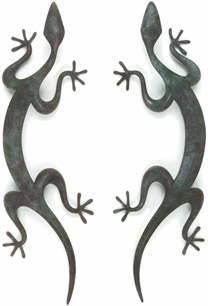

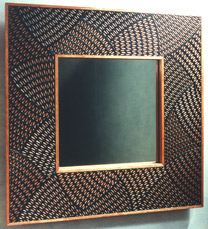

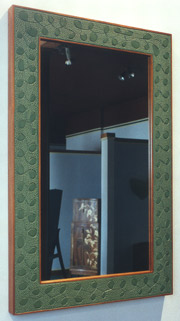

Judy Kensley McKie The Jaguar Table illustrates McKie’s great talent for combining a useful piece of furniture seamlessly with her sculptured animal forms. Rather than terminating abruptly, the long flat back of the jaguar creates a line of tension that extends to the neck of its taut form. In the detail of the head, notice the simplified abstraction that suggests the nose and eyes. As said before, the abstraction of McKie's detailing has kinship with Alaskan or African carving and little to do with the romantic realism of a Frederic Remington mountain lion. McKie will occasionally make wood pieces in small editions such as the Baby Elephant Table, which was an edition of five. Past small wood editions have included the Bird Table (1982) and the Snake Table (1987). There is a freedom that seems to come with this scale of piece for McKie, and the Baby Elephant Table was a piece cherished by gallery visitors. The utter simplicity of its form captures the contentment of simply being where it is -- truly a benign quality. The elephant stands with its legs pouring downward into the ground. What is fascinating is McKie’s ability to express and create dramatic differences through simple form. We also see this in the Jaguar Table, a similarly rooted vertical form, but one that expresses an intense energy and strength of movement. Case pieces in the show include the Pattern Chest, the Family Tree Chest, and the Flying Birds cabinets. There were also two carved mirrors, and two carved headboards. The two largest pieces in the show were a tall chest of drawers and a tall freestanding cabinet. The chest of drawers suggests a pyramid construction in that the four large bottom drawers each step in successively from the base. This stack of four drawers itself provides a base for the top tower of ten drawers and door. This piece is distinguished by the colored monotypes under glass that compose the drawer fronts. The diamond pattern of the monotypes, intentionally irregular, is reminiscent of the expressive dynamic of flag graphics. The reds, orange, and pale blues all with a light field grinning through make the colors seem weathered. The pediment and top molding are without gesture and simply frame this stack of drawers. The Family Tree Cabinet also uses monotypes under glass. Both the footed base and the crown have an exaggerated curviness that suggests the mobility of the mouth: this cabinet wants to talk. Its two full-length doors are each composed of a vertical series of four framed cartoon-like heads that mostly face each other as if in conversation. The third tier of heads contrarily face away. The sides of the cabinet also sport these framed heads, this time they're stacked vertically. Dark frames and oxblood red framing members contrast with the pale colors of the faces of these dark brunettes. In the artist’s words, "this is a goofy piece." This piece is not only a rare use of human form in McKie’s body of work, it stands as exceptional in its attitude, like a mis-struck coin. The Flying Bird Cabinet is a shallow cabinet whose carved and painted limewood doors were also the basis for a linocut series of these birds in flight. On the cabinet, the door panels occupy almost the entire front and through shallow carving of the limewood, McKie has created the lightly dimensioned detail of the birds in flight. The bird forms are in black and white with the carved lines retaining the light tones of the limewood. McKie uses deep tones of blue and green in the background field of flora to lift these birds away and give depth. Each of the four panels is unique, whereas it would have been simpler to reverse the diagonally opposite forms. The two mirrors in this show were the same scale and format, but with entirely different personalities. Formally, the mirrors are unusual in that they are squares. But much more unusual is the proportion of the square of mirrored glass to the frame itself, hardly more than 10%, suggesting more a forbidden view than a place to review and arrange oneself. It is almost like the small window in the door of a private club. Beyond this, the personalities of the two mirrors could not be more different due to McKie’s bas-relief carved patterns. In the first, four snakes coil around the mirror. Their bodies are dramatically covered in gold leaf, which is augmented by red and black pigment. The second mirror, as self-effacing as the first is dramatic, uses a delicately carved vine motif with no color differentiation in the wood surface except for the shadow cast by the carving. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Painted Poplar Jaguar Side Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bronze version of Jaguar Side Table + |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bronze Beast Bench detail |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Walnut Elephant Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

+ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mahogany, monotypes under glass Chest with Many Drawers |

Poplar, monotypes under glass, milk paint "Family Tree" Cabinet |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

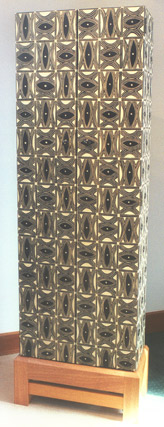

Carved & painted limewood Flying Birds Cabinet |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

+ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Carved limewood, gold leaf, milk paint Mirror with Snakes |

Carved limewood Mirror with Vines |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

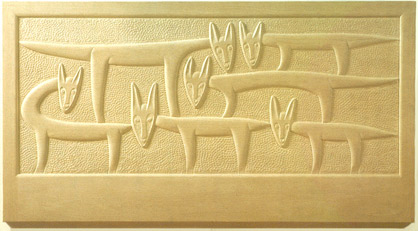

Bleached & carved maple "Watching Dogs" Headboard |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Carved maple with gold leaf & paint "Watching Dogs" Headboard + |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

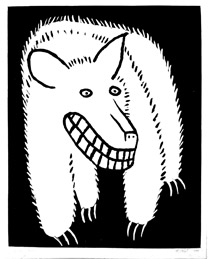

"Grinning Bear" Monotype |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Included in McKie’s show were two queen-sized headboards, each aptly called the Watching Dog headboard. The thought was to mount these on the wall with the wide bottom part of the frame at pillow height. Though individually carved, these headboards do, in fact, have the same graphic. Like the mirrors, one is polychromed and the second monochromatic but, unlike the mirrors, the bas-relief graphic in the headboards is the same. Beyond this, they are strongly different in their impact. The first headboard is carved and bleached maple, a monochrome except for the shadows thrown by the carved lines. The watching dogs stand in a strict left to right formation. The drama of the headboard is created entirely by the five faces turned 90- degrees from the body, yielding five pairs of eyes looking intently at the viewer. The second headboard has exactly the same form but the bodies of the dogs are done in gold leaf. They stand proud of a deep red painted field that is bordered by a black frame. A part of the dog’s faces, including the eyes, are painted black. In the maple version, we are mainly aware of the intent gaze of the five pairs of eyes. In the second headboard, the gold leafing of the dogs emphasizes their forms, the black of the faces de-emphasizing the gaze. They appear more as magical creatures in a dramatic landscape. The Grinning Bear monotype was one of McKie’s larger two- dimensional images from this period. It is a charming cartoon in its devilish duplicity. The bear’s grin is negated by everything else we see -- its porcupine hair, its extended claws -- as if its grinning will hide its own great sense of fright. The monotype creates a white bear on a black field. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

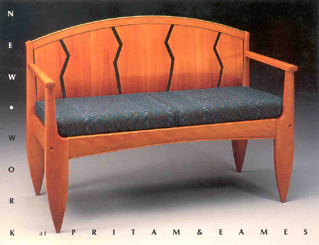

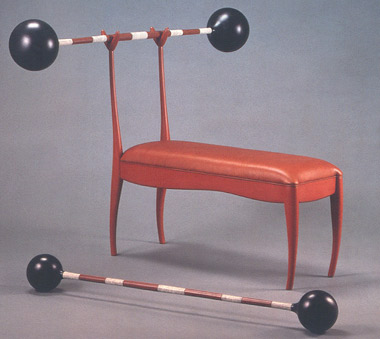

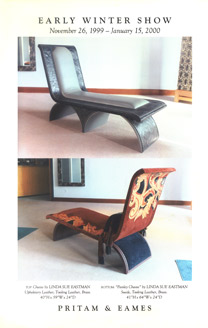

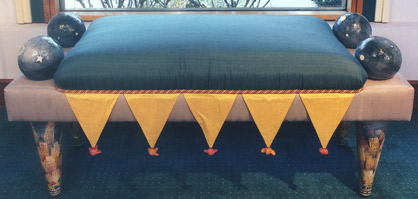

| New Work - November 1991/January 1992 |

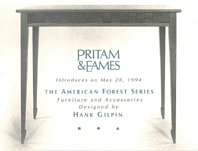

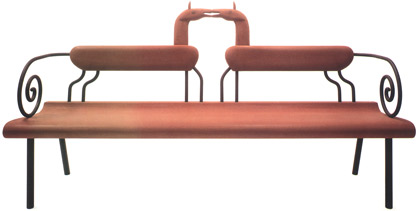

New Work The last show in a banner season came in November and bridged into 1992. The announcement piece was a pearwood settee by Don Krawczyk. Trained at RISD, Krawczyk also worked for his teachers, Rosanne Somerson and Alphonse Mattia, as an assistant, while producing his own furniture as well. The “lightning” motif cutouts in the bent laminated back panels first became part of his design language in a pair of end tables that he introduced at P&E in 1990. The thickened legs on the settee also reflect an aesthetic of the late 1980s, perhaps itself a reaction to the elegant Deco-inspired furniture that had come just before. Small settees like this one are a pleasing project for a studio furniture maker because of their scale and the opportunity to extend one’s thinking about seating beyond a chair. From the client’s view, however, it seems that the appeal of a settee is limited, perhaps settees are more associated with parlor furniture and not in keeping with contemporary comforts. Included in this show was the work of three makers trained by James Krenov: Owen Edwards, Paul Harrell, and Zivko Radenkov. The fir cabinet by Edwards has elements of Krenov’s walk-about designs as well as his classic cabinet-on-stand prototype. The three-sided facade front also reflects Krenov’s designs as well as the shaping of the legs. Its delicate glass and slender fir stiles give this piece the right aspect for a collector’s favorite small piece. The idiosyncratic combination of fir, mahogany, and yew is yet but another indication of his teacher’s approach to design through materials. Paul Harrell, an experienced maker in his own right by this time, has in this case offered a stationery box that also closely reflects the thinking of Krenov. Zivko Radenkov’s elm and satinwood cabinet is his first attempt at the oval form since his perfectly rendered 1986 cabinet. The personality of this cabinet, however, is bolder and thus champions of the first oval cabinet might not be as taken with the second. It is slightly larger, and the marquetry is less restrained. Also, the satinwood field has a luminescence that makes one think of Louis XIV, rather than the almost Zen-like restraint of the earlier cabinet. The jewelry box from Robert Ingham represents the first of a series of complex small cases to come from this English maker. Ingham had already spent many years in charge of studio production at Parnham House under the direction of John Makepeace. The Modrian-style linear graphics of the aesthetic of this box give it a different look from anything happening in the American furniture scene at this time. The delicate use of handmade hinges and distinct materials makes one think of Krenovian touches, although the strict geometry of the box would be at odds with this comparison. His use of color, in this case red dyed sycamore, expresses more of the freedom of American thinking. This strict geometry is nicely balanced by the very active, organic figure of the olive wood. Ingham explained that his own personal workplace at the school was not large, and he had learned to develop intricate highly controlled techniques that were aimed at constructing these case pieces. During this decade, it is not surprising that strong work from Hank Gilpin suddenly appears at the gallery. This was characteristic of the partners' relationship with him. The timing of the arrival of his work had less to do with the opening of a particular show or strength of the sales season, than when he could do it. In these three pieces we find both a repeated chair classic and a fresh, once-done bench: the chair a classic like a good oil painting; and the bench, fresh like a just-done watercolor. The yewwood chairs are one of a number of variants to come out of Gilpin’s Chinese-influenced, Arts and Crafts styled chairs. Here, note the back splat extends to a lower stretcher connecting the two rear legs. The arms of the chair say, “ Sit back in me,” and indeed this is a side chair rather than a dining chair. The height of the arms where the hands rest would conflict with many dining table aprons. But it is this delicious uplifting curve that gives this version of his chair its special personality. Gilpin will mostly avoid the use of an S-curve. The bench has a design simplicity that would make it at home in modernism but for the proud appearance of the pedestal tenons through the top. He uses this simple piece to show off the special textural beauty of elm. Gilpin is saying, “Just look at this. We don’t need anything more.” You could say that Gilpin has had more fresh takes and made more once-done pieces than most people working in the field.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Don Krawczyk - Pearwood Settee |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

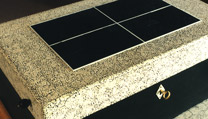

Robert Ingham - Olive, Ash, Dyed Sycamore "Ceres" Chest & Jewelry Box |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Robert Ingham - Olive, Ash, Dyed Sycamore Jewelry Box |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

David Ebner - Renwick Stool and Purpleheart Bench |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Owen Edwards - Fir, Mahogany, Yew "Story Cabinet" |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hank Gilpin - Yew Wood Chairs + |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hank Gilpin - Elm Bench |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paul Harrell - Maple Box

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Zivko Radenkov - Elm, Satinwood, Pink Ivory, Holly, Teak, Ebony Cabinet with Marquetry |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ron Puckett - Pearwood, Macassar Ebony, Curly Anigre Writing Desk |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Don Green - Ebonized Mahogany, Bloodwood, Wall Hung Chest of Drawers |

Rosanne Somerson - Fumed Oak, Maple Cabinet with Mirror |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

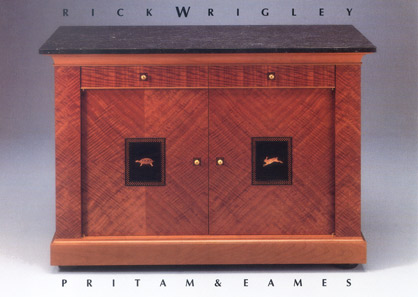

Rick Wrigley - Fiddleback Makore, black-dyed Pearwood, Maple, ebonized Maple, Gold Leaf, pique assiette Demilune Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 9 9 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

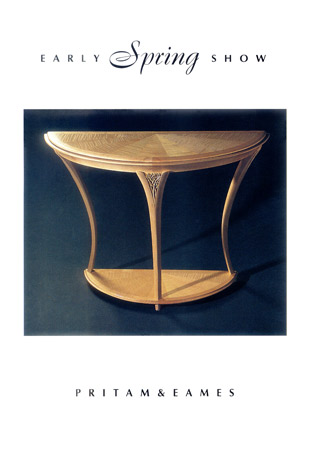

| Early Spring Show - 1992 |

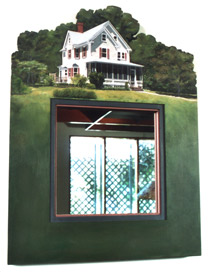

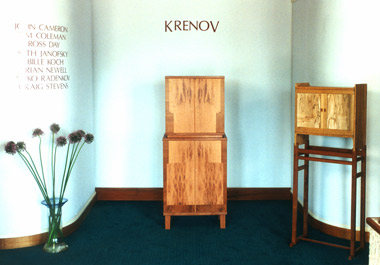

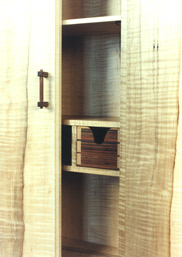

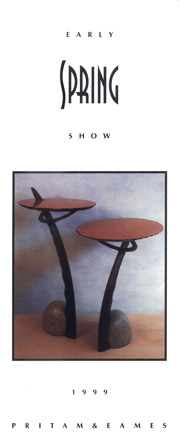

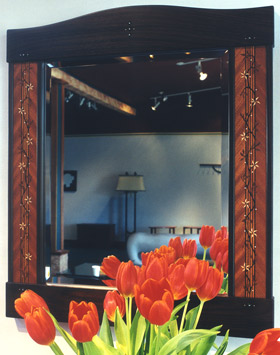

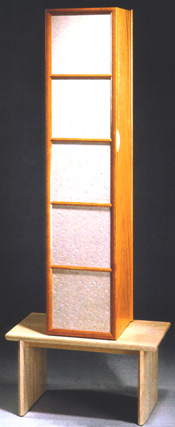

Early Spring Show The Early Spring Show (ESS) had become a standard feature at the gallery, and during the 1990s, it would be used as a more flexible format in its inclusion of makers. It also provided the gallery more leeway to continue to learn from its public’s reaction. The piece on the announcement is a three-paneled screen by Lisa Houck and is an example of stretching the group show envelope. Houck is a painter from the Boston area and not trained as a furniture maker. Another painterly inclusion in the ESS was the House Mirror by Lee Trench. Trench was trained as a furniture maker at the Program in Artisanry at Boston University, but chose the mirror to serve as her canvas for this show. She hoped that customers might like the idea of commissioning her to paint their homes as part of her mirror series. Trench’s furniture had been seen at the gallery from the mid-1980s. Side by side with this work were new arrivals from Krenov-trained makers, as well as two pieces by Krenov himself. The 1990s would prove to yield a strong flow of new cabinets from him. As was often the case with Krenov, he would call the gallery to say he had just finished a new piece or two and ask, "Are you interested?" The work would arrive soon afterwards making it virtually impossible to announce the pieces in printed material. This spring he sent two cabinets: his most recent example of a walk-about cabinet -- this one transparent from all sides, and another cabinet in which he experimented with freed and flared front door panels. The first cabinet reflected the novelty of being able to use a cabinet as a small exhibition space from the front, sides, and rear. But it was just as much about the interior space in this piece because, according to Krenov, it is the sense of space he remembers from the Stockholm Opera House. In this cabinet, the interior space was created by using a curved interior wall of spalted hickory, which provided a wonderful opportunity for the use of unusual material. In both cabinets, Krenov is experimenting with the tension of curves within frames and, in both, the use of spalted material for his shaped and coopered curves. In the “opera house” cabinet, the stand and cabinet are kwila; while in the second cabinet, he challenges us with the combination of English walnut, spalted alder, and black oak, the former material providing the framing and legs of the table/stand. The stand can be seen itself as a beautiful console with two drawers. But it is the cabinet doors that we focus on with their panels flying free of the frame on the outer sides. Note how the door pulls are used to reflect in reverse the outside curve of the flared sides. When Darrell Sewell, then curator of 20th-century decorative arts at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, visited the gallery and saw this Krenov piece, he went up and hugged it. The cabinet is in the permanent collection of that museum. Two other pieces come from Krenov trained makers: an exquisite jewelry box from Ken Frye continues his work with round and oval containers. In the lid’s delicate marquetry, he reflects more the influence of his friend, Zivko Radenkov, the interior uses asymmetry as well as curves in the design of its partitions. This time a Radenkov cabinet comes without marquetry. Atypically as well, it is wall hung. Its simplicity is also its elegance, allowing the curly ash door panels to be featured. The table lamp from Peter Thiebeault uses Depression-era glass for its upward casting shade, while the form of the wenge base reflects the then strong influence of the post- modern wave in architecture. Tweaking one of the balls on the base operates as a convenient on-off switch. John Eric Byers milk painted ash cabinet continues to show the diverse experimentations with form and color within the studio craft field. Three other makers submitted pieces representing well-honed forms from their designs. Any gentleman would prize David Ebner’s elegant mahogany valet. Its bent laminated wishbone legs demonstrate his allegiance to both Wharton Esherick and his teacher, Wendell Castle. Rick Wrigley's demilune with its aluminum-faced apron follows his previous demilune whose apron was pieced from broken dishes. The accompanying chair is unusual because of its differently styled front and rear legs. While being designed to yield an elegant chair form with decorative panache, its intention was also not to be overly complex in construction so as to be affordable. In Wrigley’s playful style, he combines the chair's fluted legs with decorative detailing in the chair back using industrial screws. The demilune uses a similar decorative feature. Lastly, included in the show was a table of scale by Jonathan Wright. Known for his fascinating rounded triangle extension tables in the 1980s, this time he opts for a post and beam structural composition over modernism and comes up with a dining table whose demeanor is more Arts and Crafts. The solid top extends well out from the legs and stretchers making for flexible seating. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lisa Houck - Oil on Wood Screen, "A Cyclone in the Area" |

Lisa Houck - Oil on Wood Screen, "A Tornado Watch is in Effect" |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lee Trench - Basswood, Oil/Milk Paint House Mirror |

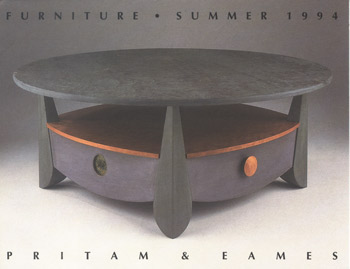

Dale Broholm - Pomelle, ebony, mahogany Mirror |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

James Krenov - Kwila, spalted hickory Cabinet + |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

James Krenov - English Walnut, Spalted Alder, Black Oak Cabinet |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ken Frye - Pearwood, Rosewood Oval Jewelry Box |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Zivko Radenkov - Pearwood Wall Cabinet |

Peter Thiebeault - Wenge, Maple Torchere |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

John Eric Byers - Ash, milk paint "Ruba" Cabinet |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

David Ebner - Mahogany, ebony Valet Rack |

Bill Walker - Cherry Armchair |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rick Wrigley - Cherry, Makore, Steel Rivets Chair |

Rick Wrigley - Bird's-eye Maple, Makore, Aluminum Demilune Table |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stewart Wurtz - Maple, Bubinga Chairs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Jonathan Wright - Cherry, Padauk, Rosewood Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

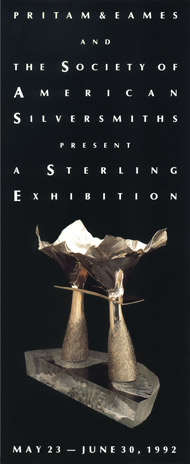

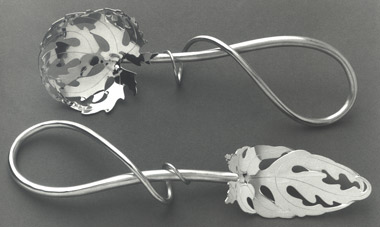

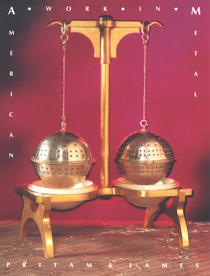

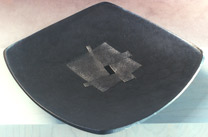

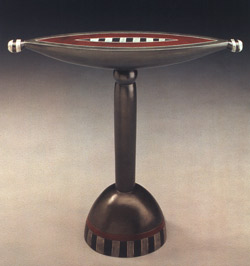

| A Sterling Exhibition - 1992 | A Sterling Exhibition In 1992, the Society of American Silversmiths (SAS) approached Pritam & Eames to host an exhibit of holloware and flatware, which they had curated. They were aware of the gallery's interest in the field of contemporary decorative metalwork. After the P&E exhibition, the silver show traveled to the National Ornamental Museum in Nashville, TN. Although the sheer number of pieces represented in this exhibit would not to be repeated at the gallery, P&E continued to host the work of a number of metal smiths in following years in an effort to develop a durable audience for American work in metal. The husband and wife team of Michael and Maureen Banner fashioned lyrical tea sets with cat-like tails as handles. Highly functional and beautifully executed, their work was appreciated by gallery clientele. Also of note was the work of Robert Butler, whose candlesticks of vermeil established a standard for metalwork. The giraffes that gracefully entwine at the base are somehow reminiscent of Renaissance metalwork. Butler's work reflects mastery over a number of technical skills that includes sculpting, casting, fabrication, soldering, cold joining of forms, and vermeil--the plating of gold over silver. The giraffes are anatomically correct, a feat itself given the scale of the work. The candlesticks conveyed several layers of messages: simple, yet technically complex and varied, functional, yet richly decorative, and lighthearted, but traditional. Kurt Matzdorf is a major figure in the field of ceremonial metal pieces, as is John Marshall, Curtis LaFollete, Robin Nichols and Leonard Urso, among others. They all had serious careers in the field of metal, and operated businesses from their studios, while supplementing their businesses with teaching. Although there was immense respect on the part of the gallery staff for astoundingly complicated pieces like Robert Oppecker's magnificent raised silver bowl, and Randy Stromsoe's' pedestal bowl, it appeared that P&E would not be able to generate sufficient public support for metalwork. However, the gallery did continue to sponsor shows of metalwork, particularly holloware, for several more years. Even today, P&E represents the holloware, flatware, and jewelry of Leonard Urso and Tom Odell, as well as the work of ten other studio jewelers. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sue Amendolara |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

John Marshall |

Michael & Maureen Banner |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Marilyn da Silva |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Robert Butler + |

Robert Davis |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Susan Ewing |

Fred Fenster |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Roger H. Horner |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

William Frederick |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Curtis LaFollette |

Thomas Markusen |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Kurt Matzdorf |

Robert Oppecker |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Randy Stromsoe |

Leonard Urso |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wendy Yothers |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| American Work in Metal - 1992 |

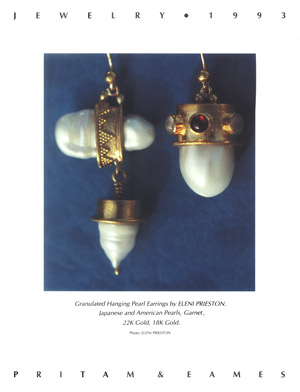

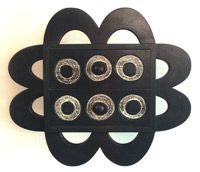

American Work in Metal American Work in Metal opened in 1992 with a lively show of work from metalsmiths working in traditional materials. Since this was an exhibition organized by P&E, the gallery partners felt they could learn a lot from their public's reaction to it. The show encompassed a spirited group who were offering a pointedly practical dimension to the work: it worked. From Jonathan Bonners' stone and copper weathervanes and Rabbit Spoons, to Mardi-Jo Cohens' Formica and silver utensils, to Robert Davis' salt and pepper shakers, it seemed like these artists were also having fun! Contrast that work with the decorative work of Mark Williams Morgan and Marvin Jensen. They were producing vessels in the technically complex Japanese tradition of mokume gane (wood grain metal), composed of many sheets of different alloys welded together and then carved and worked to produce various wood grain-like patterns. These pieces are then treated with the Japanese chemical rokusho to color the various metals used and to emphasize the pattern. It's subtle and sophisticated work. Janet Prip's bold vessels in the shape of a fish or a face brought a smile to all. Fabricated out of heavy sheets of pewter, she spent a great deal of time on her surface texture, swirling emery-paper in varying grades to create the final brushed result. Jewelry 1992 The audience was enthusiastic and supportive as the gallery continued to exhibit the work of master enamel artist Colette, as well as the wearable work of Pat Flynn, Bessie Jamieson, Tom Odell, Eleni Prieston and Joan Parcher. Pat Flynn continued to defy his public by creating "precious" wearable jewelry out of rusty steel nails, set with diamonds. He balances these raw and beautiful pieces with his ceremonial cups of pewter, silver, and gold. There was a feel of spontaneity in his work that translated across functional, decorative, and wearable lines and made his pieces extremely appealing. The gallery also hosted Vicki Eisenfeld fabricated and woven pieces of gold and silver, which she turned into alluring and utterly wearable necklaces. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Jonathan Bonner - Brass, Gold Leaf, Granite "Quaverous Cube" Weathervane |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Robly Glover - Sterling Silver "Howling Hey Man Crested Tea Thing" |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Jonathan Bonner - Copper, Granite "Sail Fin" Weathervane |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Jonathan Bonner - Sterling Silver Rabbit Spoons |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ken Carlson - Woven Copper Baskets |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Robert Davis - Sterling Silver, Onyx, Mother of Pearl "Symmetra" Salt & Pepper Shaker Set |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Robert Davis - Sterling Silver Baby Spoons |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pat Flynn - Sterling Silver, 24K Gold Plate, 18K Gold, Pewter Beakers |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Skip Gaynard - Sterling Silver Long Stem Flatware |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Carrie Harper - Sterling Silver Ice Teaspoons Bill Gudenrath - Ice Tea Glasses |

Tom Muir - Sterling Silver, Nickel Liqueur Cups |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Marvin Jensen - Mokume Gane Sphere Vessel |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Deborah Krupenia - Sterling Silver, Kuromido, 10K Pink Gold, 22K Gold, 24K Gold Plate, Japanese Copper Alloys Liqueur Cups VII & VIII |

Mark Williams Morgan - Cast Bronze with Mokume Gane inlay, colored with Rokusho |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

John Marshall - Silver & Copper Mokume Gane Helmet Form; Acrylic Base |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Robyn Nichols - Sterling Silver Watermelon Vegetable Spoon and Pastry Server |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Janet Prip - Pewter Fish Vessel |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Michel Royston - Forged Silver Ladle |

Nancy Slagle - Sterling Silver, Wood "New Mexico Teapot" |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Leonard Urso - Copper, Limestone Sculpture |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Leonard Urso - Repoussed Fine Silver Bowl + |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

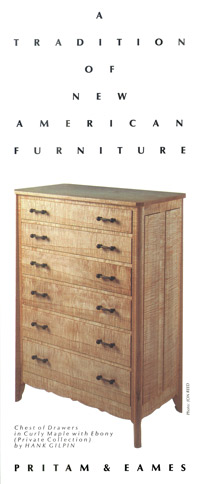

| A Tradition of New American Furniture - 1992 |

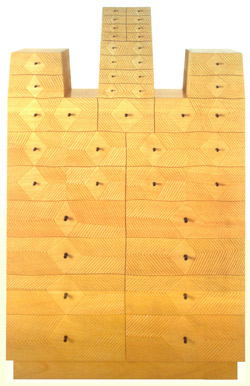

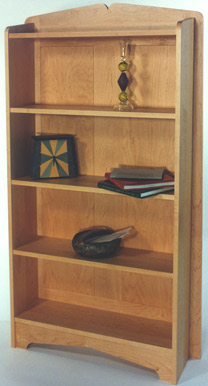

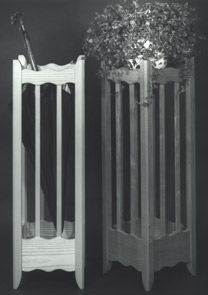

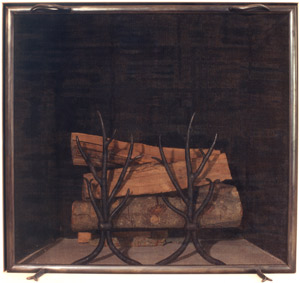

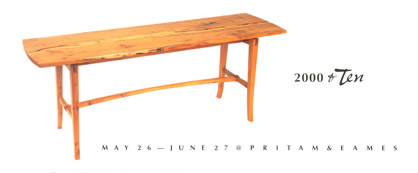

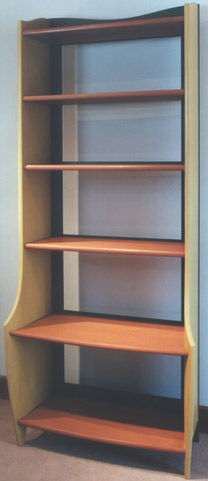

A Tradition of New American Furniture - 1992 NOTES: The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston organized two seminal exhibits that featured work from the studio furniture field: in 1989, the MFA Boston offered the New American Furniture exhibit and, in 2004, The Maker's Hand, an historical survey of 20th-century American studio furniture. Both exhibits included work by Hank Gilpin. Gilpin's curly maple chest of drawers, featured on the 1992 P&E announcement, was included in the 2004 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston exhibit, The Maker's Hand: American Studio Furniture, 1940-1990. This exhibit was organized in collaboration with The Furniture Society, an international membership organization in which Bebe Johnson was very active. In 1989, Gilpin made a wardrobe for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 1989 New American Furniture exhibit, which inspired a number of similar case pieces of scale in the following years. The spalted elm chest that Gilpin made for this P&E show was the latest in the series of his large wardrobe-like pieces. Here, the elm dictated the final proportions of the cabinet. The two six-panel doors were one of the two aspects that defined the sense of the piece. The other aspect was the design of the legs, which extended from the floor to butt flush with the underside of the top. They achieved a "friendly" corner by being set in a 45-degree angle. But they defined the feel of the piece by being tapered upwards throughout the length of the leg. This tapered leg set in at an angle had become a signature of Gilpin's case pieces, and had evolved from pieces appearing at the gallery as early as 1987. A bench, blanket chest, and small seven-drawer chest would complete Gilpin's work for the show. In addition, there was a firewood holder made from recycled church pews, which was indicative of Gilpin's spontaneous creations as well as his open-mindedness about the use of materials. By this time, John Dunnigan's work had become more detail oriented and less focused on form as in his earlier upholstered work. However, the Corner Chair, one of seven pieces submitted for this show, was a strong fusion of original Dunnigan form as well as detail. The broad shield-style back may owe something to Hucker, but the lush upholstered detailing and reeded tapered posts was vintage Dunnigan. His Cabinet with Sticks is an example of the more decorated direction in which Dunnigan's work was headed. James Schriber's featured piece, a pearwood and maple glass paneled tall cabinet, struck a formal note when compared to his folk-inspired work. There have always been a number of stylistic dimensions in Schriber's body of work, and elegant Deco-inspired pieces have held their place since the 1980s.This case piece could sit well in a room with one of his pedestal dining tables and his upholstered dining chairs. As with the Deco cabinet above, Schriber produces what he refers to as his historically referenced work. This would include his folk inspired pieces. In this show, however, it is a not folk but an architectural reference he draws upon in the leather upholstered chair and ottoman -- William Morris, in this case. Two contemporary styled consoles in cherry and ash completed his work for this show. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hank Gilpin - Spalted Elm Cabinet |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hank Gilpin - Recycled church pews Firewood Holder |

Hank Gilpin - Assorted cutoff woods Blocks |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hank Gilpin - Walnut Blanket Chest |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

John Dunnigan - Cabinet with Sticks

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

John Dunnigan - Tufted Bench

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

John Dunnigan - Bubinga, patinaed Brass, Small Faceted Cabinet |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

John Dunnigan - Corner Chair |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

James Schriber - Pearwood, Maple, Sycamore, Glass Floor Standing Cabinet

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Schriber Bubinga, Leather Chair and Ottoman |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

James Schriber - Cherry, Ash Side Tables with Drawers |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glass 1992 |

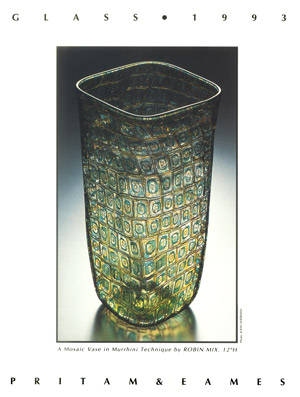

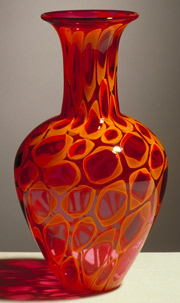

Glass '92 Art glass was a hot medium in the 1990s. The gallery's focus on functional glass forms --vases, glasses, bowls, and platters -- limited its attraction to collectors who sought mostly one-of-a-kind, non-functional art glass. Nevertheless, the color, verve, and fun of IBEX and Pinkwater Glass work found an appreciative audience at P&E. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

IBEX |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

IBEX |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

IBEX |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sonia Blomdahl |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

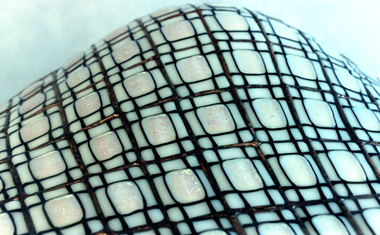

Robin Mix |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pinkwater Glass |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

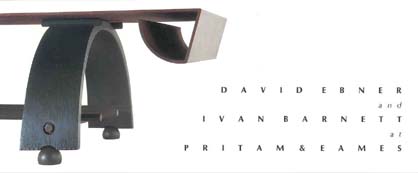

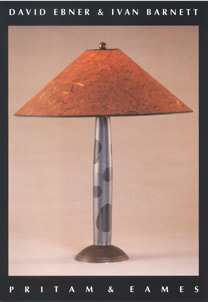

| David Ebner and Ivan Barnett - 1992 |

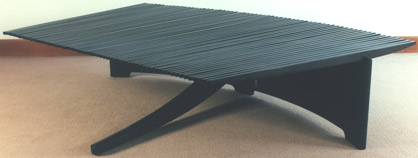

David Ebner and Ivan Barnett NOTES: David Ebner and Ivan Barnett met as draftees during the Vietnam War period. They both ended up in an Army unit dedicated to display booth fabrication. Although Barnett went on to specialize in metal fabrication and jewelry, and Ebner went on the study furniture making at RIT, they stayed in touch. In the early 1990s, they decided to collaborate and produce a body of work designed with available parts made in production for other purposes. This included the bentwood parts that Mennonites used for wheels, steel harrow disks, and tool parts, particularly handles. The oak and steel low table provided a particularly calligraphic announcement, but the favorite piece in the show was the stool. The dark tonalities of the painted finishes were a integral part of the theme, as was keeping most metal parts true to their industrial look. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Oak & Steel Low Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Oak, Steel, White Gold Leaf, Pigment Stool |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wood & Steel Low Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wood, Steel, Leather Bench #2 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wood & Steel Two Seater Bench |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

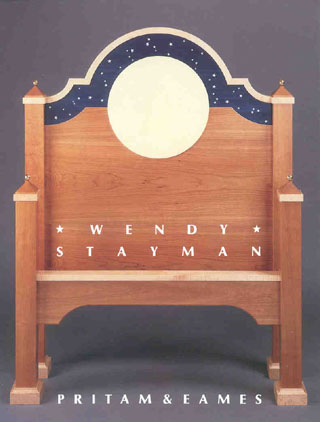

| Wendy Stayman - 1992 |

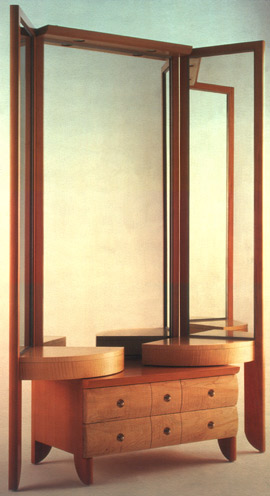

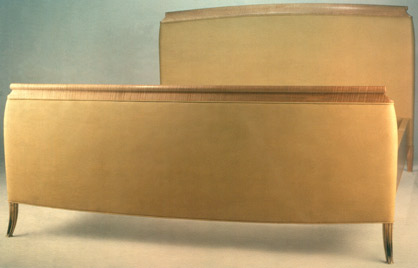

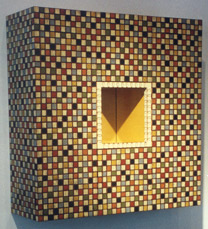

Wendy Stayman: Furniture NOTES: This was Wendy Stayman's second one-person show at P&E. Throughout the 1980s, a number of studio furniture makers had developed skills that could emulate the finest detailing of the neo-classical and Art Deco periods. These modern furniture makers had the capability to work with an extraordinary degree of accuracy in all phases of furniture construction. The quality achieved within the field, particularly by Richard Scott Newman working in Rochester, NY set high standards. The Rochester area was not the only area in the country focusing on advanced craft. The College of the Redwoods in Mendocino, CA also cultivated furniture built with the highest refinement, although the skills taught there were less technically driven. In addition to Newman in Rochester, the work coming out of the nearby Wendell Castle Studio in Scottsville, NY reached an ultra-refined level of production as well. Wendy Stayman was one of Castle's protégées and a product of his studio school. She set about to achieve her signature in work that derived from a wide knowledge of materials and techniques as a result of her background in restoration work. In this, her second featured show at the gallery, she produced a body of work stunningly detailed. From mother-of-pearl seed beads and semi-precious stones to silver, the materials matched the creative poetry of the detailing. She was not alone, however, in the number of contemporary makers to turn away from ivory and use a synthetic substitute. In her writing desk, the facade panels were covered with pattern stamped leather rather than veneer. With the ebonized cherry framing and legs detailed with imitation bone, the decorative richness was topped off by a leopard jasper doughnut shaped pull on the fall-front. Although Stayman was accomplished with elegantly evolved curves, this piece stood nicely at attention, an appropriate attitude for the light/dark motif. The Liquor Box on Table also stood squarely with perfect symmetry of form. The unbroken Cuban mahogany planes of the box itself were star-dusted with tiny seed beads, which together with the cirrus figure of the mahogany, created the subtlest of illusions. The box was hinged so that not only the top, but the front and sides opened as well.

Altogether, there were thirteen pieces in this exhibit, a significant output by a furniture maker for a featured show. Although some of the major pieces did sell, the response was not commensurate with the quality and inspirational power of the work. The handwriting was on the wall. After supporting a growing body of finely detailed European referenced work through the 1980s, the field's small collecting public was beginning to look for something else. The following year, the shallow relief pattern work of Kristina Madsen would present just such a direction. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cherry, Curly Maple, Curly Sycamore, Bolivar, Mother-of-Pearl, Brass

"Les Tres Riche Heures" Bed |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ebonized Cherry, Cherry, Stamped Leather, Imitation Bone, Jasper, Fiber

" Bon Heure de Jour" Writing Desk |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Curly Bird'seye Maple, Gaboon Ebony, Ebonized Cherry Dining Table for Four |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

+ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cuban Mahogany, Mahogany, Satinwood, Seed Beads, Brass Liquor Box on Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sapele, Curly Maple, Gaboon Ebony Bench |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Curly Sycamore, Macassar Ebony, Ebonized Cherry, Silver, Malachite, Hematite, Azurite Clock |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ebonized Mahogany, Maple, Ebony Zebra Table with Mirror |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Curly Maple, Ebony Upholstered Chair; Curly Maple, Ebony "Henson" Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Macassar Ebony, Swiss Pearwood, imitation Bone, Silver Window Seat |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bruce Volz - 1992 |

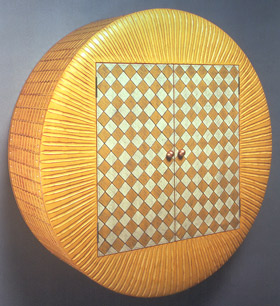

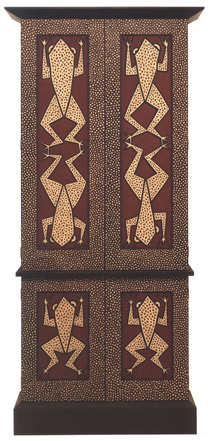

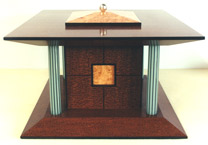

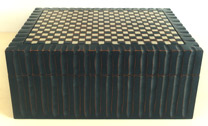

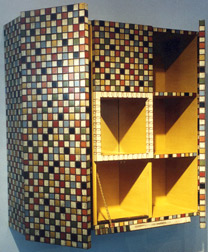

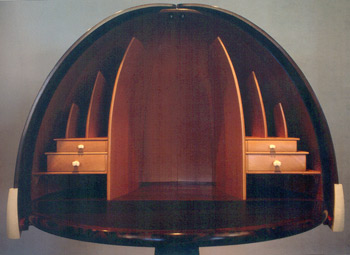

Bruce Volz NOTES: Volz's second featured show was notable for the return of his American Flyer Cabinet, a cabinet on legs whose facade was reminiscent of a legendary locomotive, and the Te Fatou cabinet, whose inspiration came from the South Seas. Although the cabinet's exact reference to Paul Gauguin is unclear, the style of the cabinet is clear. The grill of what appears to be hand fashioned dark tropical wood bars separates the user from bursts of gold dust. This, in turn, plays off a background of blackened red paint, which lends a feeling of the tropic's decay. Inside, there are upper and lower shelves with a mid-section of saw toothed, black trimmed, gold leafed drawers.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Painted Cherry, Dyed Oak, Gold Leaf, Gold, Horsehair "American Flyer 92 " TV Cabinet |

Poplar, Ebony, Mahogany, Copper, Gold Leaf "Te Fatou" Audio Cabinet + |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dyed Walnut, Holly, Copper Light |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Painted Cherry, Lucite, Sawdust "Vanishing Species" Table |

Dyed Maple, painted Poplar, Ebony, Granite Chips "Thing I" Clock |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

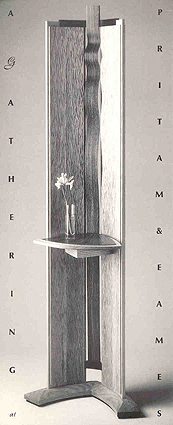

| A Gathering - 1992 |

A Gathering This small autumn show re-captures some of the surprising quality of 1980s group shows. The reason for this off-season show was simply that the work was ready. Through a series of informal telephone conversations, this group show came together. In a two-man show with Ben Mack in 1988, John Dodd introduced the idea of a movable screen/partition that can be hybridized into a cabinet, hall tree, and table as in the case of the announcement piece. Here the lightness of the ash dramatizes the ripple of the pau ferro that is suspended as a narrow central panel. The small table surface suggests a function beyond accent. The oval hall table by Hank Gilpin is distinguished by a trestle-like base, a through drawer, and a brushed and bleached finish. Like most trestles, the posts are connected by a single stretcher, which is held tight by friction fit wedge tenons. In this case, the posts are two board thickness curved solid sections. Through drawers are normally fussy since they have to work well through a double depth. The through drawer is in keeping with the oval top which itself suggests use from either side. The brushed finish was inspired by a bar in a steak house underneath the Brooklyn Bridge where the tables were wire brushed down every evening after the bar closed. Tim Philbrick was represented by a pair of his Vide Poche tables, a table form he introduced in the 1989 Ebony show. Here the material is Honduras rosewood with a vellum table surface. The single drawer is dramatized by a single ivory pull and a swag curved drawer bottom. Philbrick used what he calls "mammoth ivory" which tells the public that the material is not harvested from living species. Beautifully tapered legs give the table its tall appearance and, once again, rhythm. The table's surface is bounded on three sides by a coved border, which rises on the rear of the table to complement the swag curve of the drawer bottom. This kwila cabinet is the first work by Greg Smith to arrive at the gallery. As will be true of his future work, the quality that first strikes the viewer is its warmth and gentle understatement. In this waist high piece, two drawers are situated above two doors, which enclose interior shelves. Another distinctive feature of Smith's work is the hand fabricated metal pulls. The thick kwila veneer of the front of the cabinet uses the sapwood of the plank to the outside to give the piece a visual taper upwards. This piece is a treasure from the quiet side of woodworking. Smith worked in a commercial cabinet shop until he decided to study with James Krenov at the College of the Redwoods. Richard Newman's child's stool allowed him to break away, at least momentarily, from the discipline of his more formal pieces. The milk stool stance gives it a charming familiarity, but the spiral fluting of the legs is unmistakably Newman's panache. In keeping with the milk stool reference, the rounded tenon ends of the solid legs pierce the top surface of the stool's scalloped solid top. And yes, there is some ebony carefully veneered to the circumference of the leg tenons. A thin line of ebony, another Newman trademark, delineates its top as well as declaring the fastening wedge. The maple and ebony side table is a classic Newman design that was first seen at the gallery in his 1989 show. It appeared in that show with straight fluting of the leg. However, he was already working on the jig that would produce the reverse spiral flute that appears here. Rick Wrigley was represented in the show by a writing table and a chair in a by now recognizable style of simple classic lines and accented veneer work. His reserved neo-classical style is given a contemporary twist by the use of small black industrial screws as a repeating detail. The careful choice of veneer surrounded by ebony periling is also typical of Wrigley work at that time. His chair, a light and comfortable edition piece, extends the simple elegance of the desk. Tim Coleman also made a writing table and chair, this set in pearwood and Australian silky oak. Coleman's table structure is substantially different from the Wrigley piece in that there are three drawers. The two outside drawers are nested in the corner while the central drawer is shallower to allow for legroom. This demanded a much more complicated table frame than Wrigley's. This is an unusual and rewarding pairing of materials where the minimal figure of the pearwood is used to frame the much more active silky oak. The chair as well has its unusual aspect in that the outside stiles supporting the crest rail evolved in a ribbon like fashion to join into the sides of the seat rather than the back. This embrasure of the sitter is complemented by the gentle inward curve of the tabletop. Coleman's work is not dissimilar in feeling from early Bill Walker pieces. Coleman worked as an apprentice to Bill Walker before going to study with James Krenov at the College of the Redwoods. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

John Dodd - Ash, Pau Ferro "Table Niche" |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hank Gilpin - Oak Oval Hall Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Timothy Philbrick - Honduras Rosewood, Vellum, Mammoth Ivory "Vide Poches" |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Greg Smith - Kwila, Maple Cabinet |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Richard Scott Newman - Curly Maple, Ebony Child's Stool |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Richard Scott Newman - Curly Maple, Ebony Circular Tables |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rick Wrigley - Cherry, Makore, Steel Rivets Desk & Chair |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tim Coleman - Pearwood, Australian Silky Oak Writing Table & Chair |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Commissions - 1992 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Noel & Janene Hilliard - Sconces |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

James Schriber - Media Cabinet |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

George Gordon - Credenza |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 9 9 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

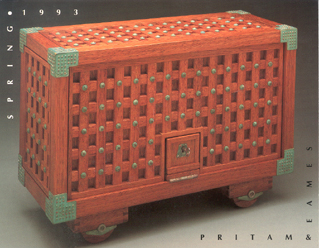

| Early Spring Show - 1993 |

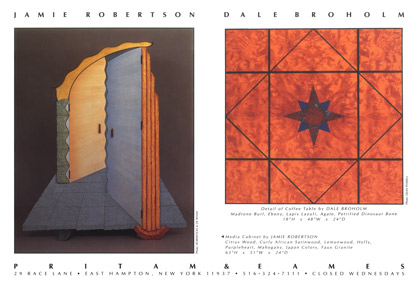

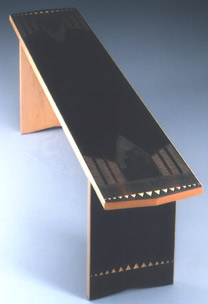

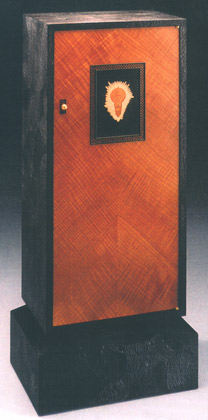

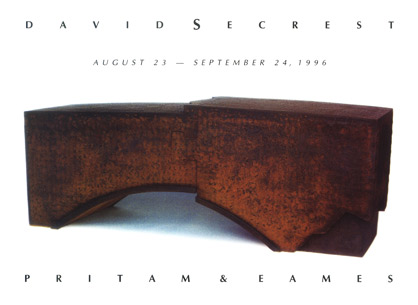

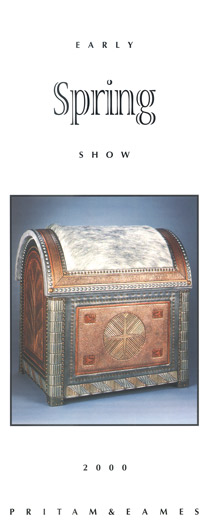

Early Spring Show NOTES: Work by talented makers continued to be sufficiently abundant in a softening market to create a spring group show with such unrepeated gems as the announcement's Strongbox by Reg Herndon. Herndon, trained by James Krenov, was at the College of the Redwoods in the 1980s, along with Zivko Radenkov. A certain design freedom accompanies occasional seating. The delight of Jamie Robertson’s Water Bench reflects this energy and brings to mind other visual confections such as the upholstered benches of Wendy Stayman and Kristina Madsen done earlier. Robertson was self-taught in furniture making, and distinguished himself with his work in veneer, which involved both marquetry images as well as sinuously curving edge banding. He will have a show with Dale Broholm at P&E in 1994. Also appearing in the 1993 show was Jane Greenberg's Tre-foil Coffee Table, which was inspired by the mobius strip. Greenberg, trained as a mathematician, often used mathematical puzzles in her furniture forms. David Secrest is the first maker associated with the gallery to use steel patterned with corroded iron, such as in his elemental Garden Bench. Jonathan Wright was known to the gallery's clientele for the originality of the design of his three-legged, triangular dining table (see 1982). One of the distinctions of that table design was its massive solidness. Here the delight of this small six- sided table is its transparency and lightness, in fact, the impression is that of fret-work. Even the bottom stretchers are composed of thin members of wood. In this piece, Wright focuses on a hexagonal design, a medium height table with six legs. The owners of this table will ultimately protect this fret-work top with a hexagonally shaped piece of glass.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Reginald Herndon - Kwila, Honduras Rosewood, Lebanese Cedar, Maple, Ebony, Brass Strong Box |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dale Broholm - Curly Maple, Walnut, Glass Rods Screen |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dale Broholm - Curly Maple, Ebony, Bubinga, cast epoxy resin , Abalone Flip Top Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Jamie Robertson - Poplar, Purpleheart, rebar, Japan & water colors "A Distant Mirror" |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Jamie Robertson - Lemonwood, East Indian Rosewood, Cherry Water Bench + |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Don Green - Douglas Fir, Milk Paint over Mahogany Cabinet |

John Dodd - Maple, Cherry Room Divider with Table |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Jane Greenberg - Mahogany, Wenge, Tiger Maple Tre-foil Coffee Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ron Puckett - Mahogany, Maple, Marble Table |

David Secrest - Wrought Iron, Steel Garden Bench |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Michael Burns - Swiss Pearwood, Jarrah Cabinet

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stewart Wurtz - Bubinga, Curly Maple, Ebony Dining Table & Chairs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Jonathan Wright - Table |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Leonard Urso - Blackened Copper Sculpture on Marble; Bennett Bean - Ceramic Pedestal; Wendy Stayman - Chair; Judy Kensley McKie - "Black Leopard" print; |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| New American Furniture - 1993 |